By shaping and promoting the Eddie Aikau myth, others—Quiksilver, mostly—stood to profit greatly…

Halfway through writing about Eddie Aikau last week, I noted that his Waimea Bay memorial service, despite being announced beforehand and held on a Saturday, drew less than 1,000 people, which seems like an impossibly low turnout but the photos don’t lie. Encyclopedia of Surfing contributor John Callahan emailed back the next morning:

A memorial service held today for Eddie Aikau, if he were to pass in the same circumstances, would draw tens of thousands of people, not the small crowd that was there in 1978. I was in high school in Hawaii at the time and the difference is, in ’78 Eddie Aikau was still a human being. It was only later, thanks to Quiksilver and the Eddie big-wave contest and the marketing around him in general, that Aikau became larger than life, a mythical Hawaiian Superman, instead of a real person with flaws and faults as well as strengths.

That sounds right. That, plus the sport in general, even in Hawaii, hadn’t yet moved too deeply into the culture at large. Not deep enough to draw tens of thousands to a 9:00 AM service, anyway.

The marketing bit, as far as transforming Aikau from respected and admired big-wave surfer to a globally recognized Hawaiian icon nearly on equal footing with Duke Kahanamoku, is worth a look.

I’m not at all saying Aikau doesn’t deserve to be so elevated. He does.

But it’s also clear that by shaping and promoting the Eddie myth, others—Quiksilver, mostly—stood to profit greatly, and that’s just what happened.

(Read the back half of this article, about how the spectacular 1974 Smirnoff has echoed down through the years, to get a sense of how the Aikau of legend has played out. SURFER Magazine bit so hard on the sell job that it credited Eddie himself, in 1974, for not just inspiring but more or less inventing the famous “Eddie Would Go” slogan for the Quiksilver big-wave contest. Hogwash. I’m 98% sure the slogan originated, fully formed and print-ready, at this exact momen in 1986.)

I’ve gone way off-topic here. Just trying to underline what Callahan said, above, that at a certain point in a marketing campaign’s growth index, the actual thing at the center of the campaign becomes flatter, smaller, less detailed.

“The slogan outgrew the contest,” I wrote in 2005, “and probably even Eddie himself. It’s definitely outgrown history.”

What I really wanted to get into here today is the last year or so of Eddie’s life, when he was still very much a real person, albeit a real person getting pulled, hard, in several directions at once.

In 1973, Gerald Aikau, Eddie’s handsome and popular younger brother, almost certainly suffering from PTSD following a difficult but decorated two-year tour in Vietnam, died in a single-car accident while driving home from a party at the Aikau house.

As late as 1976, Eddie was still feeling undone from the loss.

Meanwhile, and probably related to Gerald’s death, Eddie’s marriage to Seattle-raised Linda Crosswhite was quietly falling apart. Eddie drank more than he used to, sometimes didn’t come home, and would on occasion spend the night at Gerald’s grave.

As Clyde Aikau later put it, brother Eddie was going through “some heavy personal trips.”

Jumping ahead a bit on the timeline, Eddie was also said to have become convinced, right before setting out on the fateful Hokule’a voyage, that he would die at sea. At one point he had his sister-in-law cut his hair in the graveyard near the family compound, where he told her he had a feeling he would not be coming back.

Clyde later pushed back on the idea that Eddie had a death wish or some kind of premonition.

“He always anticipated the worst,” Clyde told biographer Stuard Holmes Coleman.”

The pre-journey nerves, he continued, were the result of Eddie’s cautious nature—which sounds odd, considering we’re talking about a man who was and is synonymous with extreme big-wave surfing, but maybe not.

“My brother didn’t take chances,” said Clyde.

He studied conditions and absolutely knew what he was capable of, and when to draw the line. But Eddie had no say in the timing or execution of the Hokule’a trip, and the whole thing was absolutely a chance-taking venture, and this may have been what had him so on edge.

But let’s turn this around.

Start looking for evidence that Eddie was not fully embedded on the dark side in the years after Gerald’s death, and things pop up all over the place.

Aikau stepped in to smooth things out following the infamous “Bustin’ Down the Door” beat-downs on the North Shore in late 1976, for starters.

(While a peacemaker at heart, according to all who knew him well, Eddie was himself not above violence; he and Clyde, both excluded from the 1970 Expression Session invite list, gate-crashed the event’s kickoff Good Karma Party with fists swinging.)

Aikau noticeably upped his game on the North Shore in 1977—at the time, an unheard-of thing for a surfer in his 30s to do—and at the end of the year, in big premium-grade waves at Sunset Beach, he won the Duke Classic, beating Mark Richards, Dane Kealoha, and Wayne Bartholomew in the finals.

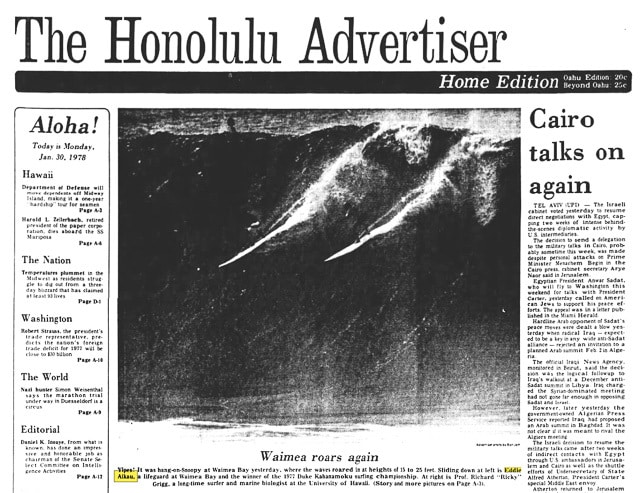

Six weeks later, Eddie was on the front page of the Honolulu Advertiser, above the fold, dropping into a huge one, with a headline reading “Waimea Roars Again.”

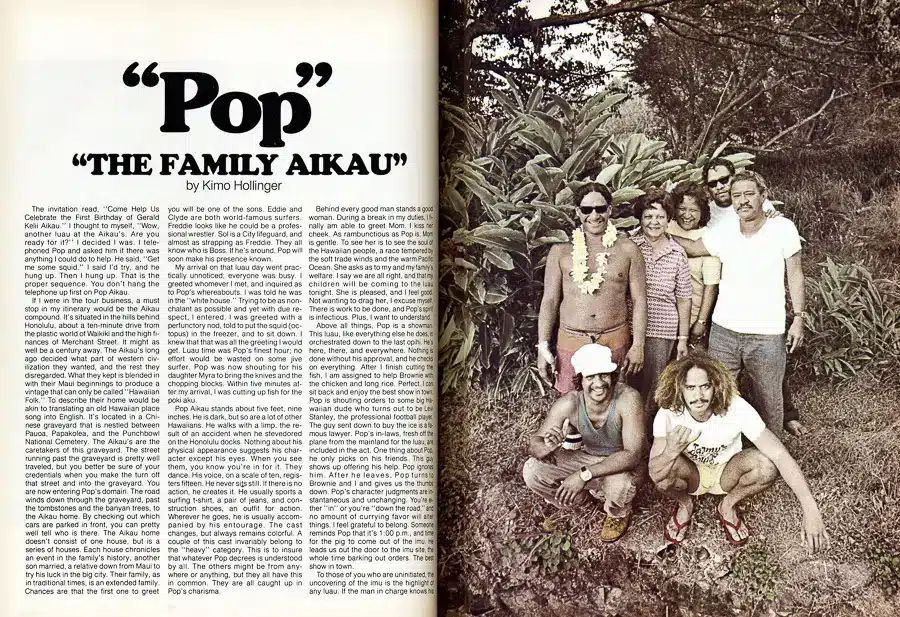

He would have been feeling great, too, about Kimo Hollinger’s recent full-length SURFER Magazine feature titled, “Pop: the Family Aikau,” which centered not on Eddie or Clyde—the famous Aikaus—but the tough bandy-legged patriarch, Soloman, who everybody called Pop. The Steve Wilkings shot that opened the article is a Hawaiian family portrait for the ages.

Finally, there was Eddie’s interest, which bordered on obsession, in being involved with with the Hokule’a, and crewing on the ship’s upcoming 1978 voyage to Tahiti.

The Hokule’a project, up to that point, was getting by on hope and pride more than results. The canoe’s first inter-island voyage, in 1975, had derailed badly in the Kaieiewaho Channel, between Kauai and Oahu, not just with the vessel swamped and in pieces, but with racial and command-structure tensions boiling over.

The boat was rebuilt on the cheap, and its first voyage to Tahiti, in 1977, while successful, saw more infighting.

But even through all of that, you could see how important and worthwhile and cherished the Hokule’a was to Hawaiians, and to anybody with an interest in Polynesian history, or seafaring in general.

Eddie certainly felt it.

Moreover, and I’m going out on a limb here a bit, the Hokule’a likely offered him a way forward, something new, something apart from and in addition to surfing, something that connected to ideas and people and culture in a way that didn’t just keep him busy at the dock and on training runs but also made his own life bigger.

On March 14, 1978, two days before the Hokule’s departed from Honolulu, Eddie did an early morning drive-time AM radio interview. The whole eight-minute segment is heartbreaking, knowing what we know. It is uncomfortable as well—the first few minutes anyway—because Aikau is so clearly nervous, almost frozen in places, as he talks about his upbringing, his career as a lifeguard, and the upcoming voyage.

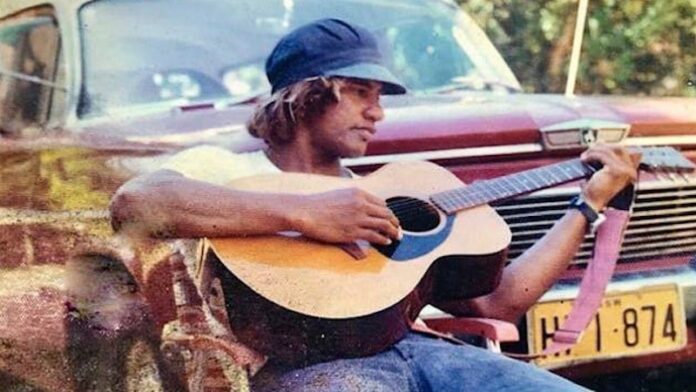

Then after a break the DJ says, “We’re going to share with you folks out there a special song written by Eddie, and it’s for the Hokule’a,” and Eddie strums his guitar for the first time, does a halting but heartfelt spoken intro, then slides into “Hawaii’s Pride,” and for three minutes we’re in a different world.

Eddie becomes another person altogether—his voice is fluid, strong, relaxed; his guitar playing is flawless, delicate, with a background mid-range drone that seems plugged into a wavelength not of this world.

How Eddie performs this feat this, with no warm-up, at 7:50 in the morning, is unfathomable to me. The song ends. “From the crew of Hokule’a,” Eddie says, “we love you, Hawaii. Aloha.”

Some of my reaction here, maybe, is just me seeing what I want or need to see in Eddie. The “heavy personal trips” that he went through in the years after Gerald’s death—an experience like that can hang off you like chains, can in fact drag you to a full stop. But it can also temper you into a steadier, more fully-realized version of yourself.

Not bulletproof. Not impervious. But better than before. This is what I think happened to Eddie during the final year of his life.

You don’t surf as well as Eddie did in the Duke, or come up with a song like “Hawaii’s Pride” and sing it with the kind of feeling he brought to the end of that radio interview, unless you’re moving forward and up.