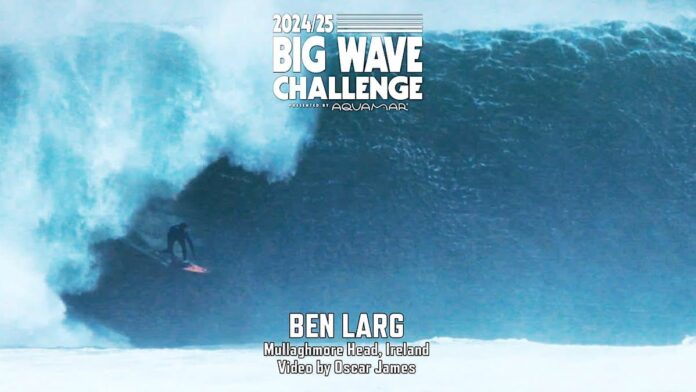

Charged Ireland’s Mullaghmore at fourteen; youngest-ever invitee to Tudor Nazare Challenge.

Ben Larg is running a little late.

We’re at Lost Shore, Scotland’s first wavepool. Set in an old quarry in Ratho, on the outskirts of Edinburgh, it’s already a boon for Scottish surfing, evidenced by the number of weel-kenned faces from the Scottish surf scene dripping and grinning in neoprene. It’s also a new coffee and artisan pizza spot for Edinburgh’s young mums and haute monde. There’s a vibe of industrial ruralism. A purposefully rusted sculpture adorns the car park. Inside it’s all beige stonework; larch cladding and glass; imported shells and white sand behind decorative walls.

Sam Howard, the photographer, was keen to get first light, but the moment has passed by the time Ben appears.

“Ben Larg on time: that’s your headline,” jokes his filmer, Oscar.

Not that anyone could be mad at him. He has a disarming type of personality, something of humility, something of innocence. On the outside, he’s an athlete who competes alongside the world’s best in the hyper-macho world of big wave surfing. But on the inside, he’s just a kid from Tiree with an affinity for the ocean.

The sea is forty miles east, but it’s a clear morning in the quarry, with the kind of biting cold that cuts through layers and into flesh. There’s a sheen of ice over Ben’s board. Getting into a damp wetsuit for photos is an unenviable position. Mannequin-like in the shallows of the concrete pool, he amiably follows instructions about his facial expressions, the way his hair is sitting, or whether his left leg should be a little further back or forward. This is the less glamourous side of being a pro athlete in a sport where content rules over competition. It’s a world Ben is still learning to navigate.

The wave machine is turned on and he slots a couple of barrels in the morning sun, before coming out of his element once again for more photos. He’s shivering, but a smile is never far away. Creatives hover around him, all with their own unshared agendas and ideas. He is in some way a pawn.

Not a pro surfer, but simply a subject. We’re all here for him, but he has little say in the proceedings. Not once does he complain.

Ben, who’s twenty now, grew up on the Isle of Tiree, a low-slung, wind-scoured dot in the Inner Hebrides off Scotland’s west coast. There are beaches of pure white sand, rolling dunes, and machair sprinkled with wildflowers. The water is so blue it can make your heart ache. On some days, it’s imbued with a sense of purest Hebridean freedom.

But there are also no trees, and gales that’ll blow you off your feet, even on a summer’s day. Like many other Hebridean islands, Tiree has an identity crisis. Traditional crofting lifestyles have long ebbed away. AirBnB logos appear like plukes down narrow lanes. Open doors that once ushered in neighbours with the Atlantic breeze are replaced with keycoded lockboxes for temporary strangers. At last census, Tiree had a population of just 653 souls.

From a surfing perspective, it’s a frustrating place. There are waves in every swell direction, but no good reef set-ups to hold them. Huge swells pound the shores in winter, the full fetch of the Atlantic Ocean bearing down. Most days, it’s simply a battle against the wind.

Craig “Suds” Sutherland, coach of the Scottish national team, lived on Tiree when Ben was born. He did some joinery work with Marti, Ben’s dad, before starting his own surf school.

‘When Ben came along we’d shove him into the waves. He just seemed to really take to it. He couldn’t really swim at that point, but pretty quickly, you could see he didn’t have much fear.”

Ben was obsessed with surfing from the start. He barely remembers a day of his childhood when he wasn’t in the water.

“From when I was about six to twelve. I swear, if I was at home I didn’t miss it, no matter if the waves were small, big, whatever,” Larg says. “Yeah, I wanted to surf every day.”

He feels changes in Tiree in the time he’s been away, just as any young person moving away sees their home with new eyes. But partly it’s that the character of Tiree has changed.

“We’ve got this beach that we always drive along. everybody does it in Tiree. They call it the Balemartine Highway,” Larg tells me. “But recently the policeman stopped me, and he was like, ‘Oh, I heard you’ve been driving along the beach’. And I was like, yeah? I’ve been doing it since I was about 10 years old!”

Ben still feels a strong connection to home, but his family started travelling to Lanzarote for the winter when he was fourteen, splitting their time between there and Blackhouse Watersports, his parents’ surf school on Tiree. Lanzarote provided an opportunity to be immersed in surfing, which was key to the flourish of Ben’s talent.

“There was a great crew of young kids surfing there,” says Iona Larg, Ben’s mum. “Ben just got on with them like a house on fire, so we just ended up going back every year.”

The reality of surfing as a career was a quiet evolution for Larg. He wasn’t even aware of competitive surfing. It was Sutherland who first suggested to Marti that they should have a go at competitions. A strong performance in the Scottish Championships in Thurso followed, giving Ben perspective on both his surfing and other areas of his life.

“It coincided with having a pretty tough time at school, so I think it gave me a bit of a motivation boost,” Larg tells me. “I didn’t really fit in with other kids. I was a bit isolated.”

The challenges and bullying Ben faced at school is a major theme of his documentary feature, Ride The Wave.

At first, the social aspect of surf competitions appealed to Ben most. He’d found other kids that were like him, a sense of community.

“I was going to the comps because I just liked hanging out with other kids that were into surfing. As we got a bit older it became more serious and you’d maybe start falling out with your mates. I kind of got out of it then.”

Ben describes himself as competitive, but not with surfing. At least, not in the sense of man-on-man. He clearly wants to push his limits, an aspect of his character that has defined him from a young age. By the time he was just fourteen years old, he had made a name for himself surfing the giant waves of Mullaghmore Head in County Sligo, Ireland.

“I’d been watching that wave in Ireland for ages, just YouTubeing it, and I became pretty obsessed with big waves,” says Larg.

“I think when the big wave stuff started coming along. That was really going to be his forte,” says Sutherland. “That’s just what he wanted to do. There’s no panicking with Ben. He’d learned to swim in the sea and in waves. He was so natural in the water, so capable.”

Recently, his status in the surfing world took another leap when he was the youngest surfer ever to compete in the Tudor Nazare Challenge, an elite, invite only, tow-surfing contest.

Ben was partnered with Andrew Cotton, Nazare pioneer and star of HBO’s “100ft Wave”.

Nazare, Portugal is surfing’s Colosseum. It’s the wave that’s garnered more mainstream interest than any other, a geographical freak show. The full power of the Atlantic is funnelled through an ancient underwater canyon, creating the largest rideable waves on earth. Added to this, the headland provides a viewing platform that allows spectators to get so close to the action, they might taste both salt and fear on their tongues.

The chances of a Scottish surfer making it to this competition are so slim it’s impossible to contextualise, nevermind one so young. Ben’s dad, Marti, wanted to find a piper for the cliff. It would’ve made a stirring scene: bagpipes on the headland as a twenty year old Scotsman dropped down the face of a forty-foot wave.

Despite Larg’s inexperience at this level, his comfort was clear.

The rapport between him and Andrew Cotton propelled them to a third place team finish. More impressively, in the individual competition Larg finished third, ahead of far more established names such as Nick Von Rupp, Kai Lenny and Ian Walsh.

“He seemed more nervous on dry land,” says Cotton, “as soon as he was in water he was on another level.”

It wasn’t just Larg’s surfing ability that allowed him to perform at Nazare.

The most underrated skill in tow-surfing is driving the jetski, according to Andrew Cotton.

“Ben is way beyond his years at driving a jet ski. Usually I’m looking to team up with guys like in their 40s, or late 30s. I trust them to put me into a wave but also to rescue me. They have the experience. But Ben has that. And I don’t know how he’s got it so young, but he has got it.”

I ask Cotton what elements of Larg’s character allow him to place his trust in a tow partner so young.

“Well it wouldn’t be his punctuality,” he laughs. “He’s just very comfortable in the ocean. And that’s when you get the best out of a performance, when it’s fun, it’s play. He’s not worried about the waves or his surfing or his ski driving skills. And he’s just happy to play in that zone.”

If surfing is Ben’s first love, vehicles come a close second. It’s this affinity for machinery that makes the world of tow-surfing such a tantalising prospect. A youth spent on the lawless, Mad-Maxian beaches of Tiree paying dividends.

“My dad was always into motorbikes and I got into bikes as well when I was two years old. My uncles all chipped in and bought me a wee 50cc quad bike. I remember being two and I was cutting about naked on the thing all the time.”

His skills and performance in a competition of this magnitude should have vaulted Ben Larg to superstardom. But big wave surfing is not a lucrative sport, and the economics just don’t add up. There were (inexplicably) no prizes for second or third place, just four thousand Euros per team if you’re invited (before tax). The veneer of a professional career in surfing is glossier than ever.

Until recently, Ben had very little engagement with Instagram. But he’s been forced to capitulate to the power of personal branding. It’s part of the game. What he posts is largely handed over to his filmer, Oscar. I ask him if he finds the communication part of his job tough. He picks up his phone, flicks at a couple of messages from his managers still awaiting a response and sighs.

“Ah, fuck, I’m alright, eh, but there’s a lot of messages, you know?”

If Ben Larg has been afforded any advantage, then it’s certainly in the family that surrounds him. A sense of warmth and vitality extends to the whole family. To Marti and Iona, his parents; to Robyn and Lily; his younger sisters. Even to Gary, the scruffy family Parsons Russell Terrier. Without Marti and Iona’s willingness to let their children lead an alternative lifestyle, none of what Ben has done would have been possible.

They arrive at Lost Shore a day after Ben, having driven all the way from Portugal. For a family used to being on the move, a journey like this doesn’t faze them. In the back of Marti’s van are two motorbikes, four surfboards, a raclette machine, and a full leg of Basque Country ham.

“It’s a nightmare but, because I cannae leave Gary in the van on his own cos he’ll tan the ham”, he laughs, Dundonian roots still very much evident in his accent.

Ben has been a fulcrum for family decisions. All the Larg children have attended an online school since 2018, eschewing traditional education for travel and experience. It wouldn’t necessarily work for everyone, but it has for them.

Ben’s eighteen year old sister, Robyn, currently works at Lost Shore, instructing surfing. She’s making inroads to a surf career of her own, recently making headlines for being the youngest British woman to surf Nazare.

Lily, the youngest at fifteen, is more into horses than surfing. She also has a clear entrepreneurial spirit, telling me about the food cabin she intends to set-up at Balevulin beach this summer.

“We just want Ben and the girls to be happy and enjoy what they’re doing,” says Iona. “I think that that’s all anybody really wants for their kids.”

That’s not to say there aren’t challenges. There’s the worry that any parent would have watching their children engage in risky activities. There’s knowing how hands-on to be in helping Ben navigate an evolving and uncertain career. And then there’s making sure he’s on time.

“Yeah, that’s a struggle. Always has been,” laughs Iona. “It’s a learning process.”

But despite Ben’s strong support network, the grind of forging a career weighs on him. The constant checking and questioning of forecasts. The tug of war between content and authenticity. The travel. The comps vs clips conundrum. The pitching of ideas to brands. The emails, meetings and messages.

“He needs to be thinking, ‘I want to be the best in the world’,” says Andrew Cotton when I ask him what advice he might give Ben in navigating a career.

Regardless of the future, Larg is already the most accomplished Scottish surfer in history.

“It’s absolutely incredible”, says Craig Sutherland of Ben’s career. “If you’d told me that was going to be the outcome I’d never have believed it.”

Because of him, there’s a generation of young surfers in Scotland who might see a different future for themselves. As coach of the national team, Sutherland sees this up close.

“Some of the kids now are thinking there could be possibilities if Ben’s done it. They all look up to him, and he’s always really supportive of them.”

What Ben Larg does next is still uncertain. He’d like to spend time exploring the potential for undiscovered waves in Scotland, on some of the more remote islands, perhaps. And he’d love to make longform video content. His dream is something like a surf version of The Art of Flight.

But as Andrew Cotton points out, reflecting on his own early motivations, in big wave surfing, the goal can be gloriously simple.

“I’ve always thought I’d get a wave and it would change my life.”

This remains the dream for many big wave surfers, and it’s no different for Larg. The right wave, on the right day, at the right time. There’s no longer any planning, or early morning photoshoots, or emails to deal with. You simply need to go.

And for this, Ben Larg would be on time.