The following is an excerpt from Chapter 3 – A Waterman in Los Angeles of Surf and Rescue: George Freeth and the Birth of California Beach Culture by Patrick Moser (Copyright 2022 by Patrick Moser); it is featured here with the permission of the author and of the University of Illinois Press.

Freeth arrived in Southern California by mid-July. He first tried surfing at Long Beach “but found the rollers there unsatisfactory.”1 So he and Kenneth Winter, who had just finished his junior year in high school at Oahu College, traveled north to meet with Lloyd Childs, the Los Angeles representative of the Hawaii Promotion Committee. Childs had worked with Abbot Kinney before, and he arranged to have Freeth and Winter contracted for the surf exhibitions in Venice.2 Winter was a member of the Healani Boat Club and had performed with Freeth at the Hotel Baths when the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce visited Honolulu the previous March. Childs had been on that trip, so perhaps the three men had met during his stay. Winter probably saw the trip as a chance to take a summer vacation in Southern California and earn some easy money. Freeth himself likely had no idea what his plans were that summer other than to give surf exhibitions. His options were open as far as travel goes, and he seemed to be considering working his way east at the end of the summer.3

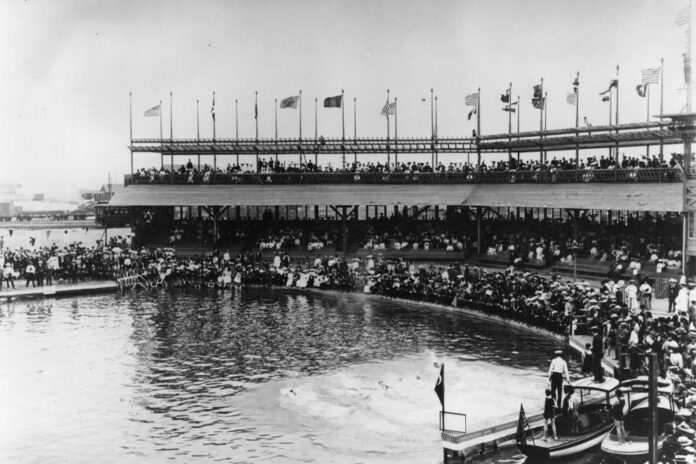

From his time at Atlantic City and San Francisco’s Sutro Baths, Freeth would have recognized the carnival-like atmosphere along the boardwalk in Long Beach, a resort area known as “The Pike.” The coastal towns to the north—Redondo Beach, Venice, Ocean Park, Santa Monica—had all devel- oped similar beachside attractions to lure Angelenos out on weekends and holidays. Visitors enjoyed bowling alleys, shooting galleries, roller-skating rinks, roller coasters and other rides, along with various food vendors. The centerpiece of all the resorts, however, was usually an elaborate bathhouse, or “plunge.” The one in Long Beach had been open since 1902—a two-story, Greek-columned affair that offered heated saltwater pools and baths, bathing suit rentals, and private dressing rooms. It had opened on July 4 of that year, the same day Henry Huntington completed laying electric trolley tracks to the city.4 A one-way trip to Long Beach from downtown Los Angeles took about an hour—twenty-two miles or so, directly south. The week before Freeth and Winter arrived, a heat wave drove an estimated thirty thousand people to the beach cities on the electric trolleys for the July Fourth holiday, most of them going to Long Beach. The local railroads carried another fifteen thousand to the coast.5

Long Beach was ahead of its time in placing a lifeguard station on the beach. The service had begun in 1902 with the opening of the Long Beach Bath House. It was reported that in the first five years, only nine lives had been lost in the surf directly in front of the bathhouse, most of them due to “cramps.”6

But in 1907 the season began in the worst possible way. A railway con- ductor named Arthur Custer, twenty-two years old, drowned within sight of his wife and others on the beach. The young couple had been married only seven months. The two lifeguards, Carl Witte and F. Moody, along with several volunteers, ran the lifeboat out, but it capsized in the heavy surf. By the time they righted it and rowed out, Custer had already gone under. One of the witnesses on the beach that day was Thomas Saeger of Los Angeles. His nephew, a young attorney named T. Wright Robinson, had drowned four days earlier. Saeger “has come down to the beach nearly every day,” the Los Angeles Herald reported, “hoping that the waves may speedily give up their dead.”7 Family members had little recourse at the time other than to wait for the tide or current to beach their loved one.

Venice had similar problems. Four days after Art Custer drowned at Long Beach, two fishermen drowned within sight of two thousand people on the beach. Their launch, Boston, had capsized in heavy surf. The two men hung on to the craft for several hours while the crowd grew and rescue attempts were made, but by the time a swimmer finally reached them, the two men had slipped under. The captain, a local man named John Cochran, was later found lashed to his boat with ropes and fishing nets. Apparently he’d tied himself to the craft, unable to swim.8 The large crowd was indicative of the growing popularity of beaches in Los Angeles and its booming population. Not only had the drownings occurred on a Sunday afternoon in the summer, but Venice was the closest beach to downtown Los Angeles. One-way trips on the Venice Short Line cost fifteen cents and took under an hour.

Editorials quickly appeared in the local papers, pleading for more life- guards. One bystander in Venice, George E. Squires, reported that the “so- called lifesavers stood there doing nothing while the men were drowning.

. . . They seemed to have no understanding at all of their duties.”9 In the face of such tragic incidents, the Los Angeles Times summed up the area’s lifesav- ing situation: there was no organized lifeguard crew—federal, state, local, or even volunteer—at any point along the Santa Monica Bay; the lifeguards from the bathhouses were not trained to rescue shipwrecked crew in heavy surf and had no lifesaving equipment beyond a boat, lines, and buoys; and a single reel and lifeline had been installed on the beach between Venice and Santa Monica for emergencies but with no crew to practice using it. The paper thus declared that local drownings were “unavoidable.”10

Abbot Kinney, the founder of Venice, decided that such drownings were avoidable. He advertised Venice as the “most desirable beach resort in the world.” Men drowning off his pier in front of thousands of spectators—including members of the city trustee board—was not only a preventable tragedy; it was also bad for business. He enlisted the help of Percy Grant, an experienced captain who ran the boating concession in the resort’s canals, to form the Venice Volunteer Life-Saving Corps. They started meeting in late May and placed orders for two new lifeboats and a catamaran with airtight compartments especially designed for rescues. They gathered a list of possible volunteers, many of them employees of Kinney.11

At their first tryouts on the evening of June 13, however, one of the as- pirants, Charles Watson, drowned in the surf. Watson had come to Venice with the circus as a bareback rider but stayed on to work for Kinney. The Los Angeles Herald reported, “Watson’s drowning probably constitutes the most heartrending tragedy that was ever enacted within sight of the beach here and took place less than 400 feet from where more than a score of members of the life corps stood absolutely unable to in any way prevent his untimely death.”12

Watson’s dory had capsized as he and another volunteer, Andy Anderson, tried to turn it around in heavy surf. There seemed to be a question of whether Watson even knew how to swim. He slipped under despite Anderson’s at- tempts to reach him. The waves rolled Watson to shore twenty minutes later. They worked over his body for three hours but could not resuscitate him. Civic groups later held a benefit for his wife, left in “straightened circum- stances,” so that she could travel back to New York with his remains.13

Watson’s drowning typified the general lifeguarding situation in the Los Angeles area. The bathhouses hired lifeguards for the plunges and beach, but their training, knowledge, and experience were limited. Most of them were not prepared to save swimmers or fishermen who ran into trouble in heavy surf. They simply lacked the basic skills to carry out rescue operations in stormy seas. Even in calmer conditions, their lifesaving and resuscitation techniques were rudimentary at best.

When Freeth and Winter arrived in Venice, people were amazed when they saw them standing on surfboards and riding waves. But Freeth had so much more to offer. His depth of knowledge about the ocean and his broad aquatic skills, developed over two decades of working and playing in the Pacific, made his presence in this small resort town a cultural flashpoint for California beach culture. Over the next three years, Freeth injected Native Hawaiian cultural attitudes about the ocean into the Southern California psyche. He showed Angelenos the many pleasures to be had in the waves and taught them skills of swimming and diving that allowed everyday beachgoers to skirt the ocean’s many dangers. They all knew Freeth came from an exotic place—the Hawaiian Islands—but his Anglo features and genuine interest in their well-being made his lessons as enjoyable and accessible as Hawai- ian hapa haole music, which would become a fad in concert halls across the country the following decade.14

Yes, Freeth could certainly surf. As for the rest of his talents, it wouldn’t take him long to show people what he was truly capable of.

**********

The author and Surf Simply would like to thank Dr Patrick Moser and Heather Gernenz of the University of Illinois Press for their assistance with the article. Patrick will be presenting the book at the Redondo Beach Main Library on July 16 and at the California Surf Museum on July 27.