A classic story of sliding doors or how two men of equal ability and from the same beach can veer down wildly different paths.

During a business trip to Sydney in 2009, I went to Bondi to try to find my old friend, Ant Corrigan.

The town had changed quite a bit since my last visit in 1984—the pubs and their punters, the milk bars and their pinball machines, the junkies and their smack—all replaced by bistros, boutiques, and bankers.

Located less than five miles from King’s Cross, Sydney’s notorious red-light district, Bondi is the closest beach to the city center.

The horseshoe-shaped cove stretches roughly a kilometer from the pool at the Iceberg’s Swimming Club at the south to the rocks at the north.

Unlike Sydney’s more exclusive northern beaches, up until the 1990s, Bondi was an extremely diverse working-class town. It is lovingly referred to by its residents as “Scum Valley” due to its filthy, polluted water.

During the 1970s, after a bad storm, it was not unusual for the beach to be littered with faeces, used condoms and syringes.

I figured that the most logical place to begin my search for Ant would be at the Rip Curl wetsuit shop on Campbell Parade behind the beach park. After all, Ant in his custom made red and yellow wetsuits doing Larry Bertleman-like turns, on Micheal Cundith’s Sky Surfboards, made him the alternative poster child of the 1980s.

The surfer behind the counter told me that Corrigan, like most of the old Bondi locals, had moved from the coast and that my best bet was to look for him after 4 p.m. in the Off-Track Betting section of the Royal Hotel on Bondi Road.

The Royal was one of the few remaining old school pubs in this now upscale area. I got there early, spotted some concrete, paint, and plaster-spackled surfers my age enjoying after-work schooners and approached them.

When I asked about Ant, it quickly turned into a reunion of sorts. A few schooners later, and one of my new friends was on the phone, putting out the word that “Corro’s seppo [American] mate Pete was in town and looking for him.”

Word got back to me that Ant worked for Qantas and was finishing up his shift at the airport but would meet me at the Royal the following night.

Ant Corrigan and I had shared some magical, carefree days surfing northern New South Wales in 1984 before the pressures of adult life encroached upon us.

More than one of Australia’s greatest surfers, Ant was a classic Aussie larrikin who had more in common with Ned Kelly than the hipsters who had taken over his hometown.

Those who were born and bred in Bondi grew up fast.

“Skullduggery was common, so Southside surfers had to be apt and on their toes. Dealing with rioting, rapes and murders and cops and robbers, were all part of the city beach lifestyle,” wrote Matt Ellks in his novel Scum Valley, “It was an area where street credibility went a long way. You could have all the money in the world, but if you didn’t have street-cred, you were nothing. In this environment, your daily exploits were the measuring stick of who you were.”

Long before the Fords, Corrigans, Horans, Crams and Webbers, there were iconic Bondi watermen like Keith “Spaz” Hurst, Jack “Bluey” Mayes, Kevin “The Head” Brennan, and the gladiators who manned the North Bondi Surf Lifesaving Association who would set the standards for generations of Bondi watermen to come.

World War II veterans like Adrian Curlewis, who survived three years as a Japanese POW in Burma, built the surf lifesaving associations along military lines, with “battalions,” patrol captains, and served as the organization’s president for forty years (1935-1975).

The first phase of Australian beach culture was defined by the volunteer groups that sprang up along the coast to reduce the number of drownings at the nation’s treacherous beaches. These clubs gathered regularly for surf carnivals that featured swimming, paddling, running, surfboat, and surfski competitions.

The day usually ended with beer-soaked sausage-sizzles, the inevitable interclub “blues” (fights), and then truces sealed by more beer and laughs.

Founded in 1906, the North Bondi Surf and Social Club was much more radical than your typical surf club.

“North had all the characters,” said former Australian surfing champ Robert Connelly, “The renegades who wouldn’t do community service, wouldn’t patrol beaches on a Sunday because they wanted to go surfing at South Bondi. They were more stage wrestlers and boxers. I’m talking ‘Hollywood George’, the wrestlers and the nightclub bouncers coming down to stay fit.”

Qantas engineer Vic Corrigan was a member of the prestigious North Bondi rescue-boat crew. The punter’s (bookie’s) son grew up in Bondi in a house with racehorse stables. Corrigan married Maureen Hallahan, and by the early 1960s the couple had three children: Steve, Cathy, and Ant.

The young Corrigan family spent most of their free time at the beach. “We just loved the water,” said Cathy Corrigan Clapoudis. “We used to go down to the Bondi baths all the time.”

After Vic and Maureen divorced, the single mother moved into a friend’s Bondi apartment, where Steve and Ant shared a room but spent most of their days surfing and skateboarding. When the Ford brothers formed the invitation-only Panache Surf Club, they invited Steve Corrigan, one of Australia’s hottest up-and-coming surfers, to join.

The Ford brothers knew that some of Australia’s best surfers were in nearby Narrabeen, and if the Bondi mob was to successfully compete against them, they had to measure themselves against them on a regular basis.

Although it was only eighteen miles north, Narrabeen was a world away.

“The Harbour Bridge, and the miles of road in between,” wrote Ellks, “protected northside beaches from a lot of city heat.”

Not only were the waves better, but there was also a hotbed of surfing talent where some of Australia’s greatest surfers—Col Smith, Terry Fitzgerald, and Simon Anderson—were all about to make their marks in Hawaii, South Africa, and California in the new sport of professional surfing.

The Ford brothers bought a VW van, and before dawn each morning, they filled it with Bondi’s best surfers and drove to Narrabeen.

Two of the surfers who were usually in that van were Steve Corrigan and his diminutive, toe-headed brother.

“I used to surf most mornings, Monday to Friday, before primary school,” Ant recalled, “Those trips were unbelievable. I was surfing with the best surfers in the world. It was like a competition every morning. I was privileged to be a part of it.”

Ant Corrigan got so good so young, that it would take many years for his peers to catch up.

“The name, Corrigan, say from 1973 to 1977, over the course of two brothers, meant a ton to the hopes and dreams of surfers everywhere,” wrote Derek Hynd, “The Corrigans were a strong representation of why things burned for a whole generation of career-destined Australians down the track.”

Bondi’s surfing population exploded in the early 1970s, and there were now three main factions: the Hill Crew, the Wall Crew, and the Rock Crew.

The elite “Hill Crew” occupied the grass hillside overlooking the beach.

According to Cheyne Horan, one of Australia’s greatest professional surfers, “If anyone walked up the hill, they had to have a reason. So, if they weren’t with the crew, you’d pelt them with milk cartons.”

In the water, the surfing hierarchy was even stricter.

“In those days,” recalled Horan, “we weren’t even allowed to speak to the older guys. You weren’t allowed to paddle out the back. Bondi had a big thing like that. We weren’t even allowed to surf in the south corner if they were in the water. They paddled out and guys just paddled in.”

1974 was a big year for Australian pro surfing, and many had high hopes for Steve Corrigan when he traveled south to Torquay to compete at the Bells Beach Rip Curl Pro. Although his competitive performance was mediocre, word of his free-surfing and his roundhouse-loop cutback spread quickly.

“Surfing wouldn’t draw the lines it draws now without Steve Corrigan. Mick Fanning, Kelly Slater, Tom Curren!” exclaimed Cheyne Horan, “all those guys have got a bit of Steve Corrigan in them.”

While some criticize the Fords for being straight and square, there is no denying their success in turning Bondi into a breeding ground for competitive surfing talent.

At the 1976 New South Wales Championships, Bondi surfers took 1st through 3rd places in every division. At the Australian Titles, Bondi also swept every division with Ant Corrigan winning the under-15 division and Cheyne Horan winning the under-19.

“So it turned out that this hot little crew of guys in Australia are possibly the best kids in the world,” recalled Horan with pride.

Although Cheyne was slightly older than his doppelgänger, Ant Corrigan, they became fast friends. The pair surfed together all day, every day, their only breaks being for what Horan described as the “really dodgy sandwiches, worse than 7-Eleven.”

In true Bondi fashion, Ant figured out a way to remove their lunch from the vending machine in the pool hall across from the beach without paying.

“We’d get a couple of tasties, a couple of free drinks,” recalled Corrigan, “and then fuck off.”

When the pair wasn’t surfing, they were skateboarding, which Horan believes accelerated their surfing progression.

“We tried to do things that the old guys couldn’t comprehend. That’s where Ant and I got into 360s and different things like that.”

After Horan won the Australian Titles in December of 1976, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a professional surfer. In order to do this, he needed a bankroll and approached Steve Corrigan, who worked as a plumber, for an apprenticeship.

Corrigan told Horan that he could start the following week after he returned from a ski trip to the Snowy Mountains. Tragically, Steve fell asleep driving home from the mountains, and got into a head-on collision with a bus. His two passengers survived, but Corrigan died from his injuries.

While Bondi’s tight-knit surfing community was shattered by the loss of their most promising surfing son, nobody took it harder than Ant.

“After Steve passed, it really affected him,” said Ant’s sister Cathy. “They shared a room and it was very hard on Ant. He often stayed with other friends and family who sort of adopted him after the accident. Mum was so beside herself, she was happy if he was happy.”

“It was just a devastating time, a really sad time for everybody,” recalled Horan. “To me it was the start of manhood as us grommets set aside childish ways to face the realities of life. From that day on, my brother and I, we took Ant on as a brother. We were always there for him. We forged that brotherhood, more than just a friendship.”

After his brother’s death, Ant took a more Dionysian view of life, and the city became his playground. At sixteen Corrigan doctored his birth certificate so he could work at the Chevron Hotel in Kings Cross where his friend’s mother ran the notoriously raucous bar with an iron fist.

“Everyone had a lot of respect for her, she wouldn’t take any shit from any sailors,” Ant recalled. “My boss was a gay bloke and she just said to him straightaway, ‘Keep your hands off him, Barry, if I see you go near him, I’ll rip your nuts off!’ Barry didn’t look at me twice after that.”

When the U.S. Navy ships docked in Sydney Harbor, they were bussed straight from their ships to the giant pub and nightclub where a platoon of Sydney’s heaviest bouncers were always ready for battle.

“The Yanks would come when their ships landed,” said Corrigan. “There was a bit of friction between us and the Yankees at the time. I saw some heavy brawls at that joint.”

By the end of his 16th year, Ant knew the working girls in the Cross by name and enjoyed après-work nightcaps at Bourbon & Beefsteak, the CIA’s haunt in Sydney.

Ant was still one of Australia’s best surfers, but unlike his friend Cheyne Horan, he was neither enamoured nor impressed by pro surfing.

Seventeen-year-old Horan, in only his second year on the fledgling International Professional Surfing tour, was ranked second in the world. Horan and Corrigan’s sponsor, Rip Curl wetsuits, convinced Ant to enter the Rip Curl Pro at Bells Beach.

Cheyne Horan got up in the dark on a cold Victorian morning to cheer on his friend, but when he got to the beach, Ant was nowhere to be found.

“They’re calling out his name, I’m waiting at the contest for him,” said Horan, “and he doesn’t show up. That’s typical Ant. I know Ant and I know that he doesn’t really care about the contest scene as much as we do.”

Horan figured that his friend had gotten drunk or met a girl, and just let it slip by.

More than a decade later, he asked Ant about that fateful day at Bells. Although Corrigan made it to his hotel in nearby Torquay, his ride to the contest site never showed up.

“So that’s how Ant Corrigan missed out on being a pro surfer—the guy not showing up to take him to the beach,” said Horan, who then drew a deeper meaning from the missed ride. “It’s nature taking its course. It was never going to be his destiny and it wasn’t.”

While much has been made about the missed heat at Bells Beach, Corrigan’s real denouement with pro surfing occurred a few years later at the 1979 Stubbies Pro at Burleigh Heads.

After a blistering 3rd place finish in the trials, Ant should have qualified for a spot in the main event. However, contest organizer Bill Bolman decided to give one of the overseas competitors his place.

“I surfed in trials to even get to the trials,” says Corrigan. “They kept knocking me back until I ended up 16th reserve.”

Toward the end of the championship heat between Hawaiian Dane Kealoha and Australian world champion Mark Richards, an angry Corrigan paddled out and waited in the channel for the contest to end.

The second the horn went off, he sprint-paddled deep into the lineup.

“I just knew where it was going to break, and this solitary 4-foot wave come out of nowhere.”

In front of the giant crowd watching on the beach, Ant caught the wave of the day.

“I knew what I was going to do,” he said. “I was gonna show right off! I start spinning roundhouse 360 after roundhouse 360.”

When Corrigan got to shore, “I kicked me board up under me arm and marched up the beach. Me hair hadn’t even gotten wet. People were going, ‘Why weren’t you in the contest? Why weren’t you in the contest?’ I said, ‘Ask Bill Bolman!’”

Ant returned to Bondi and his job at the pub. Pro surfing was less disillusioning to him than it was boring.

“I had a gutful, I wasn’t getting anywhere I wanted to go,” he recalled, “I was a bit of a reb and free spirit and had more fun surfing with friends and probably got better waves than the pro surfers, just traveling with mates to secret spots and had a wonderful time with no hassles.”

Ant’s sister Cathy was always slightly amazed when she received her brother’s postcards from exotic locales like Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Central America, and Hawaii.

Before I met Ant, I saw a photograph of him that is forever seared into my memory. Resplendent in his custom red and yellow, short-sleeved Rip Curl wetsuit and matching board, Corrigan is carving a perfectly timed bottom turn around the hollow section of a thick, overhead right.

Unlike Peter Townend’s more famous and melodramatic soul arch, Ant’s is closer to Terry Fitzgerald’s functional “power arch.”

Hands behind his back, right clutching left, eyes focused on the next section like a Formula One driver charting his line through the chicanes, Corrigan’s posture is perfect, his rail is buried, and he has speed to burn.

There is no wasted movement; it is a photograph of mastery.

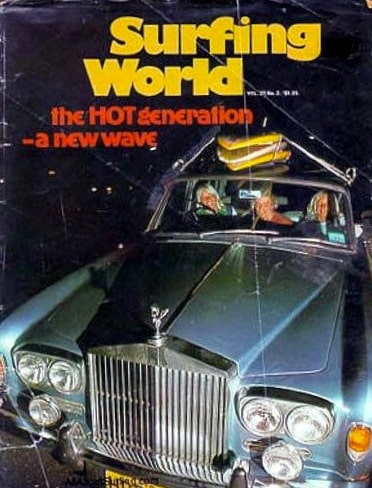

The most famous image of Ant, however, was a 1977 Australian Surfing World cover shot that featured a Rolls Royce Silver Cloud with a quiver of single-fins strapped to the roof. Future world champion Tom Carroll, Cheyne Horan, and Ant sit in the front seat.

The caption reads: “The HOT generation—a new wave.”

Tom Carroll would go on to win multiple world championships, Cheyne would have a remarkable pro career, and Corrigan walked away from it all.

Bondi’s Ron Ford was probably referring to Ant when he wrote that Bondi and its neighboring beaches had “an abnormally high percentage” of Australia’s best surfers, but for some their hearts were not in it, and many were pursuing “more traditional Aussie pursuits.”

While Ant Corrigan’s early competitive exploits spoke for themselves, his surfing fame was spurred by a series of Australian Surfing World magazine covers.

Unlike the American magazines of the time, Bruce Channon and Hugh’s McLeod’s magazine featured long, lavish, beautifully photographed stories about adventurous young Aussies exploring their continent’s vast, untamed coastline.

For a California teenager like myself, who preferred long-range Baja expeditions and camping on coastal ranches to colored jerseys, these images spoke to me in a way that the American magazines did not.

Above all, they reminded me that surfing’s frontier was alive and well.

I think that I was the only graduate from my posh West LA private school who did not go to college immediately after graduation.

Instead, I worked two jobs, one in construction and the other in California’s underground economy, saved every penny, and planned to leave for the surfing safari of a lifetime that would officially begin on my nineteenth birthday.

Each morning I dragged myself out of bed at 4 a.m., looked at the Air New Zealand ticket pinned to my wall and reminded myself that this pain would only be temporary.

Days after my nineteenth birthday, I moved into shaper Michael Cundith’s house at 8 Broken Head Beach Road and never looked back.

Cundith, then a surf-stoked 38-year-old bachelor, put me through a six-month crash course in single-man living that served me well until I married two decades later.

Felix Unger to neighbor George Greenough’s Oscar Madison, the Santa Barbara expat had lived in Australia since the ‘60s and was a meticulous craftsman who shaped some of the most advanced surfboards in the world.

Although the triplane hull was popularized by Tommy Curren and Al Merrick’s Channel Islands Surfboards, Cundith, Greenough, and Chris Brock had invented and perfected it many years earlier at Byron Bay’s Sky Surfboards.

Cundith’s small house/surfboard factory, conveniently located across the street from Broken Head Point, was a constant hive of activity during the 80s.

Surfers from all over Australia and the world congregated around his kitchen table and shared pre-surf “cuppas” (coffee or tea) and “cones” (bong hits), and post-surf “cold ones” (beers) and “hot ones” (joints).

A week before the 1984 Stubbies Pro at Burleigh Heads, Mike Cundith and I drove to the Byron Bay train station to pick up Ant who was MC’s star rider at the time.

He would spend a few days with us dialing in his boards and then head to the Gold Coast, an hour north, for the contest.

When the overnight train from Sydney pulled into the station, a short, broad-shouldered man with blonde hair and a blonde mustache walked down the stairs and onto the platform.

Before Cundith could shake his hand, a pretty girl grabbed him by the arm, spun him around, planted a big kiss on his lips and asked, “Aren’t you even going to say goodbye?”

Ant smiled, flashed us a cat-that-ate-the-canary grin, shook my hand, and said, “G’day Pete, now how are the banks at Broken?”

First impressions are rarely wrong, and during the week Ant Corrigan stayed with us he made quite an impression.

From Broken Head to Lennox, to Yamba and beyond, when Ant paddled into a surfing lineup, the former Australian cadet and schoolboy champion stood head and shoulders above the pack—really any pack—anywhere.

By the time I met him, he was a streetwise man of the people who stood outside and above surfing’s caste system.

In the days leading up to one of Australia’s most prestigious contests, pro surfers from all over the world descended on our house on their way up from Sydney to the Gold Coast.

One morning, I was roused before dawn by a loud commotion. I came out of my room and found a white-haired stranger wearing a black bowler hat who looked like a cross between one of the Droogs from Clockwork Orange and a Waffen-SS Obersturmführer hovering over Ant, who had been asleep on the floor.

Ignoring me, Hawaii’s Tim “Tazzy” Fritz was loudly demanding a cup of coffee. The white Hawaiian had once placed in the Pipe Masters, and both in and out of the water he is remembered as one of the heaviest surfers of the 1980s.

“G’day big fella. What’s this I hear about a cuppa?” Ant said as he stood up, extended his hand, and when he said, “Ant Corrigan,” the menacing Aryan suddenly turned into a star-struck teen. “You’re Ant Corrigan?” he gushed. “Australian Surfing World is my favorite magazine! I’ve been following your career for years.”

We gathered around the kitchen table where the big Hawaiian chased his coffee with more powerful stimulants that he had smuggled in from home. Then, just as quickly as he had arrived, Fritz was gone.

He would bomb out of all the contests, but Tim Fritz would become famous with bouncers from Queensland to Victoria. Fritz died under mysterious circumstances at the age of 24 in 1986.

Although the waves Ant and I surfed during the week leading up to the contest were great, the afternoon pool games at the “RSL” (the Return Service League is the Australian version of VFW) and his crash course on Australiana were better.

Ant invited me to join him on the Gold Coast for the Stubbies contest. A few days later, we drove north in my VW van. Ant told me to stop at the first hardware store he saw and emerged with plastic tubing of various sizes.

Next stop, Woolie’s supermarket.

As I filled our cart with our week’s provisions—tea, instant coffee, cereal, milk, cordial syrup, Arnott’s “bikkies” (cookies), cigarettes, and “Red Head” matches—Ant went to the pastry section to hunt down a cake decorating set.

“The metal tips,” he explained, “make perfect cones” [bong bowls].

Our last stop was the bottle shop where we bought slabs (cases) of Tooheys New beer.

Our holiday flat overlooked the almost flat Burleigh Heads lineup. We had traded perfect, uncrowded surf at Broken Head for tiny waves clogged by the world’s best surfers.

The serious pros like Tommy Curren and Tom Carroll were staying sharp by surfing nearby Duranbah, but Ant couldn’t be bothered. Instead, he held court at our flat as old friends from Bali, Hawaii, and all over Australia, streamed into our flat at all hours, for their choice of a cuppa, a cone, or a cordial.

I pitied our neighbors, California’s teetotaling Christian world champion Tommy Curren and his young, French wife, Marie. They had no choice but endure our noisy presence. Ant was the yang to the unflappable Curren’s yin.

While I didn’t realize it at the time, Ant was teaching me by example not to take a surfing contest more seriously than a reunion with your old friends.

“When Ant is one of your mates,” said Cheyne Horan, “he’s a great mate. He won’t shirk on telling you that you need to wake up to yourself. He might say things sometimes to you that cut to the bone, but you need to know it. I think that’s one of the things that I love about Ant. He’s said things to me that no one else will ever say and that’s what I’ve always appreciated about our friendship.”

When we weren’t entertaining guests, we were playing miniature golf and eating Big Macs at McDonalds, the only place in Australia at the time where hamburgers weren’t covered with beets and mountains of shredded carrots.

Nighttime only meant one thing: The Playroom. Located on the Gold Coast Highway in Palm Beach, the Playroom was one of Australia’s great music venues during the 1970s and 1980s where bands like INXS, Cold Chisel, Midnight Oil, Australian Crawl, Men at Work and many others got their start.

“If you fell on that carpet, you would probably need a tetanus shot,” recalled one regular, “It was also so sticky with all the grog and who knows what was spilt on it.”

In the early 80s, pro surfers did not travel with coaches and shrinks; it was a much more bacchanalian time. The Hawaiians had a hard time keeping up with the Aussies in the beer drinking department but more than made up for it when the inevitable “blues” (fights) punctuated the end of the night.

A few bleary days and nights later, the Stubbies Contest began in tiny, substandard surf.

Ant easily won his heat, but seconds after the final horn sounded, a set wave appeared on the horizon. He knew that if he rode the wave, he would be disqualified but took off anyway, and linked bottom and top turns all the way to the beach.

It was another Pyrrhic victory, but at this point in his surfing career, Corrigan couldn’t have cared less.

“Them is the breaks, yeah, that’s my life,” Ant recalled, “It was unreal, we had a wonderful time.”

Unlike many surf stars at the time, Ant was remarkably absent of ego.

In the ocean, he was one of the best surfers in the world, but once his feet touched the sand, he was just another bloke from Bondi. This was both a blessing and a curse.

(Editor’s note: Peter Maguire is a surfer, war crimes investigator and author ofThai Stick: Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade (movie rights optioned by Kelly Slater), Law and War, Facing Death in Cambodia and Breathe, the new bio on jiujitsu icon Rickson Gracie. Ain’t much ol Petey can’t do. This story appears on Pete’s substack Sour Milk, subscribe, it’s free etc.)