Wake up; open instagram; peep perfectly backlit waves in a tropical locale; check local surf report; see onshore slop; cry; go back to bed. This is the unfortunate morning routine for most surfers.

A quick e-surf leaves wondering how those waves are always perfect, and how people score them seemingly all the time. Meanwhile, the waves in your area rarely get anything like those picturesque beauties.

The truth is, those tasty waves like Pipeline, Uluwatu, J-Bay, etc, have special features that — when aligned with the right conditions — create world-class surf. But even those breaks have moody days.

It takes the right conditions to make a perfect wave, and timing that perfection takes some knowledge, practice, and of course luck. Here we take a look at some of the main factors that shape the end product of waves in our guide to different types of surf.

Swell Types

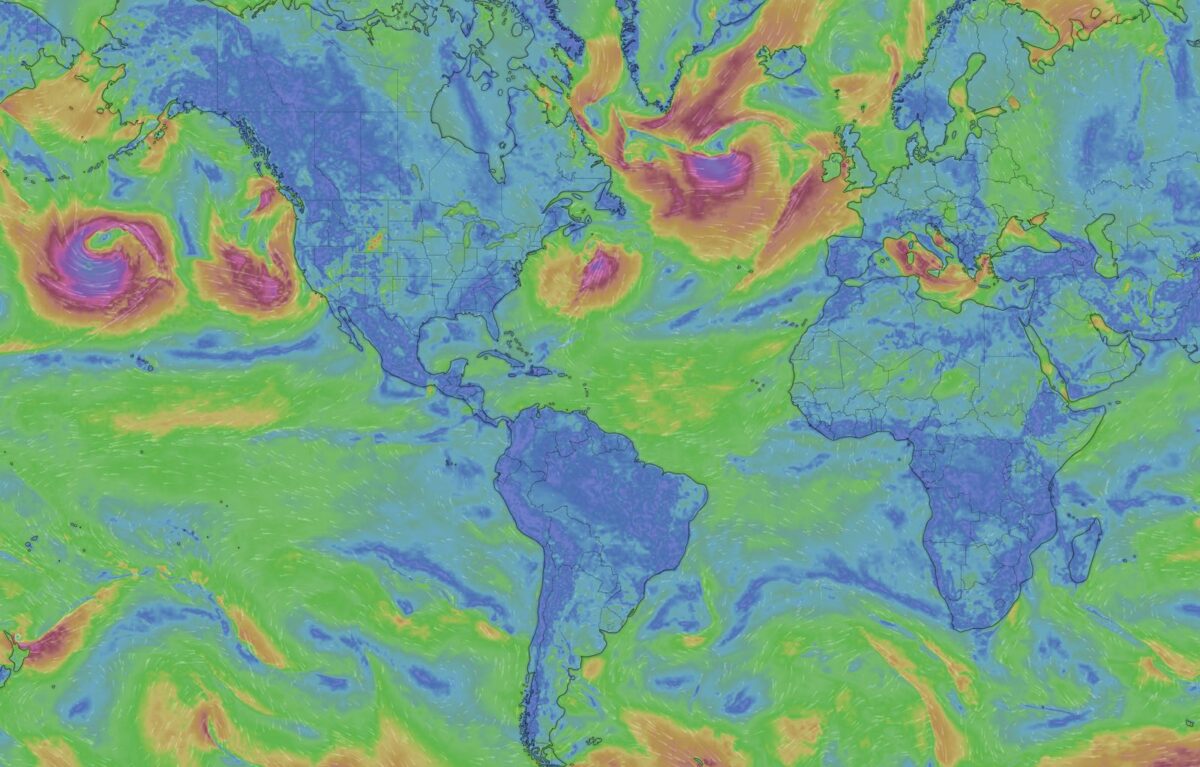

Swell is a cosmic dance of transferred energy. The source of that energy is wind. And the direction a swell comes from plus the distance it travels influences the quality of the surf.

For starters, there’s two main types of swell: ground and wind. While both still energetically come from wind, they are distinguishable by the distance traveled to get to a destination (i.e., the surf).

- Windswells occur closer to shore — say within several hundred miles — and have shorter periods. Swell periods are measured in seconds and denote the time it takes for a wave to pass a fixed point. Short period swell under 10 seconds won’t travel very far and remains closer together as it marches in as sets. Overall, windswells tend to be more unorganized and are spaced closer together.

- Groundswells come from much longer distances — like across the sea — and have longer periods. A groundswell of 11-20+ seconds can form well-organized and powerful waves. Notably, the longer intervals between sets can be tricky. In one moment, the ocean can seem flat, but then a long period swell freight trains through the lineup.

When you compare the two types of swells you can get wildly different results in wave heights.

For example, Magic Seaweed explains that a 4-foot wave from a short period windswell of 10 seconds might only show up at your break as a 6-foot wave. Meanwhile a 4-foot wave from a long-period groundswell of 20 seconds could stand up as a 9-foot wave. Notably, as the wave period approaches the height of the wave, the wave becomes steeper.

- Hurricane swells bend the rules. Hurricane swells are supercharged windswells that still have shorter periods, but pack a lot more punch. Hurricanes that produce these swells may be closer to shore — or even enter the coastline — so they are potentially dangerous and can cause serious damage.

Direction

The direction of a swell tells you where the swell comes from. For example, a north (N) swell comes directly from the north, and a south (S) swell comes from the south. The direction of a swell is important relative to the positioning of your local break. In general, breaks that face the direction of the incoming swell can better accept it.

The direction for certain waves are critical. For example, Pipeline tends to perform best on longer period northwest (NW) swells, with a trend towards the more westerly direction, reports Surfline. As the swell passes an outer reef, it refracts to Pipe. Meanwhile Backdoor turns on during the more northerly norwest swell with a shorter period.

The easiest way to learn about your local break and swell direction (outside of asking someone who surfs there frequently) is to use a surf app. Check the swell direction and then go to your break. Eventually you’ll figure out which direction brings in the type of waves you like.

Or if you are core and still have an AM/FM radio, dial in to your local NOAA station and listen hard; listen good.

Winds

Winds also have direction and are oriented in the same way as swell direction. So a north wind comes from the north. There’s three main types of wind direction:

- Offshore winds blow out to sea. If you face the ocean, offshore winds blow at your back, tickling that tear in your pants. Offshore winds are ideal because they groom waves and fully express barrels. Too much offshore wind can make it hard to paddle into waves because they blow you off the back.

- Onshore winds blow towards land. They agitate the sea and the soul surfer’s resolve. If you face the ocean, onshore winds will blow into your face. They tend to make waves crumble and fall over themselves instead of disemboweling. But onshore winds offer an advantage to aerial surfing because they help the board stick to the feet.

- Cross-shore winds blow parallel to shore. If you face the ocean, cross-shore winds will slap either the right or left side of your face. If you are into cross-shore winds, then you probably dabble in kite or windsurfing.

The direction of the wind will determine whether or not it is cross, off, or onshore relative to your local break. Take Pipeline for example again. Southeast (SE) winds blow offshore at Pipe, which performs best from northwest (NW) swells. The incoming swell gets combed by the opposite direction wind to form those perfect barrels.

Learn your cardinal directions; apply them to swell and wind.

Types of Ocean Bottoms

When it comes to the seabed and surfing, there are three main ingredients to note.

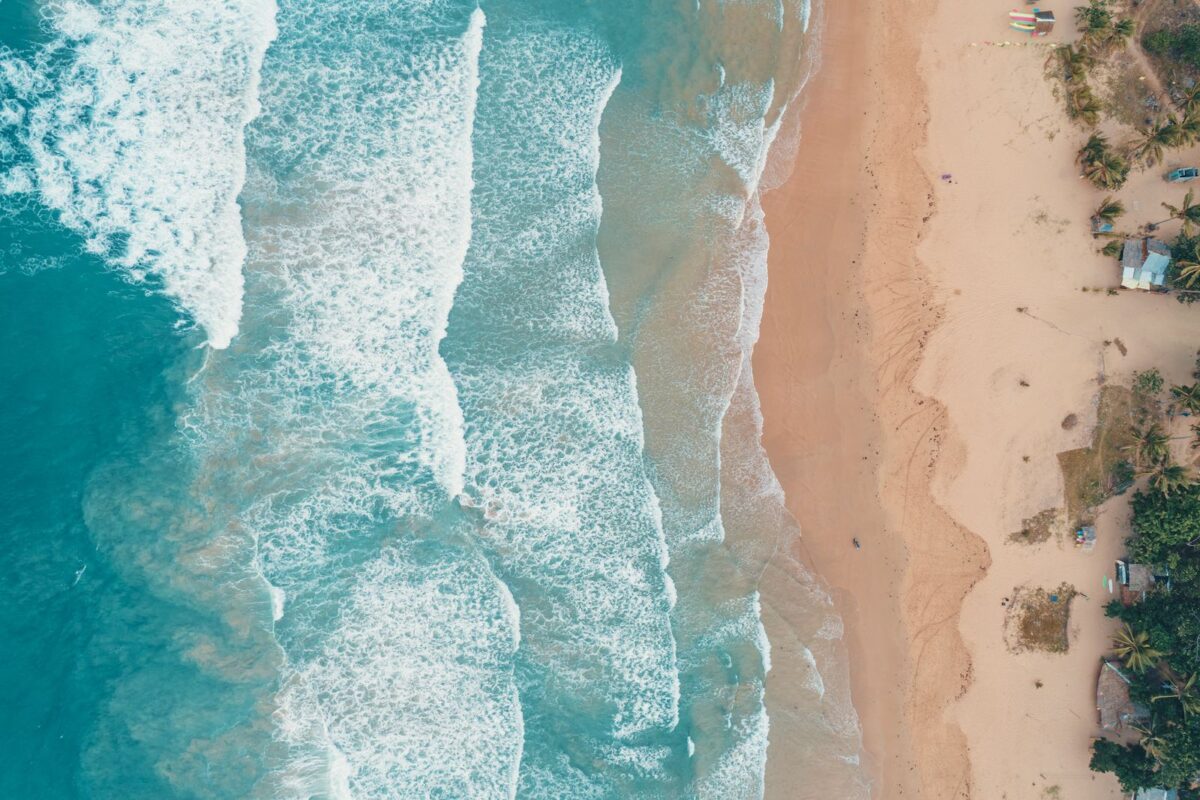

- Sand bottom beaches have relatively soft seabeds. Shifting sandbars can create changes in the waves.

- Reef / rock bottoms are more solid seabeds that make the wave more consistent but also more deadly in terms of wipeouts.

Of course, these substances do not always exist in mutual exclusivity, and your beach may have a mix of any or all of them.

Types of Surf Breaks

There are different types of surf breaks, each with its pros and cons.

- Beach breaks like Duranbah, or D-bah, have soft sand bottoms. D-bah is a special beach break because of the rock walls that funnel swell into the lineup. Lineups at beach breaks are spread out, so surfers can come from any direction. Heads up.

- Shoreys, slang for shorebreaks, are those like Oahu’s Sandy Beach that have a dramatic shift in seabottom close to the shore, causing waves to unload in shallow water or directly on the beach. Shoreys are back breakers.

- Rivermouths like Mundaka come alive when a river deposits sand and creates an organized wave. Rivermouths are notoriously sharky and can have dirty water.

- Reef breaks like Pipeline unload over a coral reef (or rock) and produce a more consistent wave. Hitting the reef or being trapped in a pocket of the reef/rock are hazards.

- Point breaks like J-Bay are the result of a landmass that causes the wave to bend and wrap around the point, creating extremely long rides. They feature sand and/or rock/reef bottoms. Long rides and long paddles can leave you with noodle arms and burnt legs. Paddle outs can be dicey if you mistime them and land you a date with the rocks.

- Offshore breaks like Cortes Bank occur far offshore, and are the result of a reef jutting up from the depths near the surface. The risks of surfing XXL slab waves in the middle of the ocean are self-explanatory.

Notably, many breaks have multiple points where the waves are surfable. In basic terms, the outside break is the wave that forms farthest from the shore that day. If you hear someone say they “made it out of the back,” it means that they paddled to the outside break.

Waves can also break on the inside (and yes, sometimes even the middle). The inside break is usually where beginners learn to surf, groms pick off leftovers, and experienced surfers avoid crowds and score when the time is right.

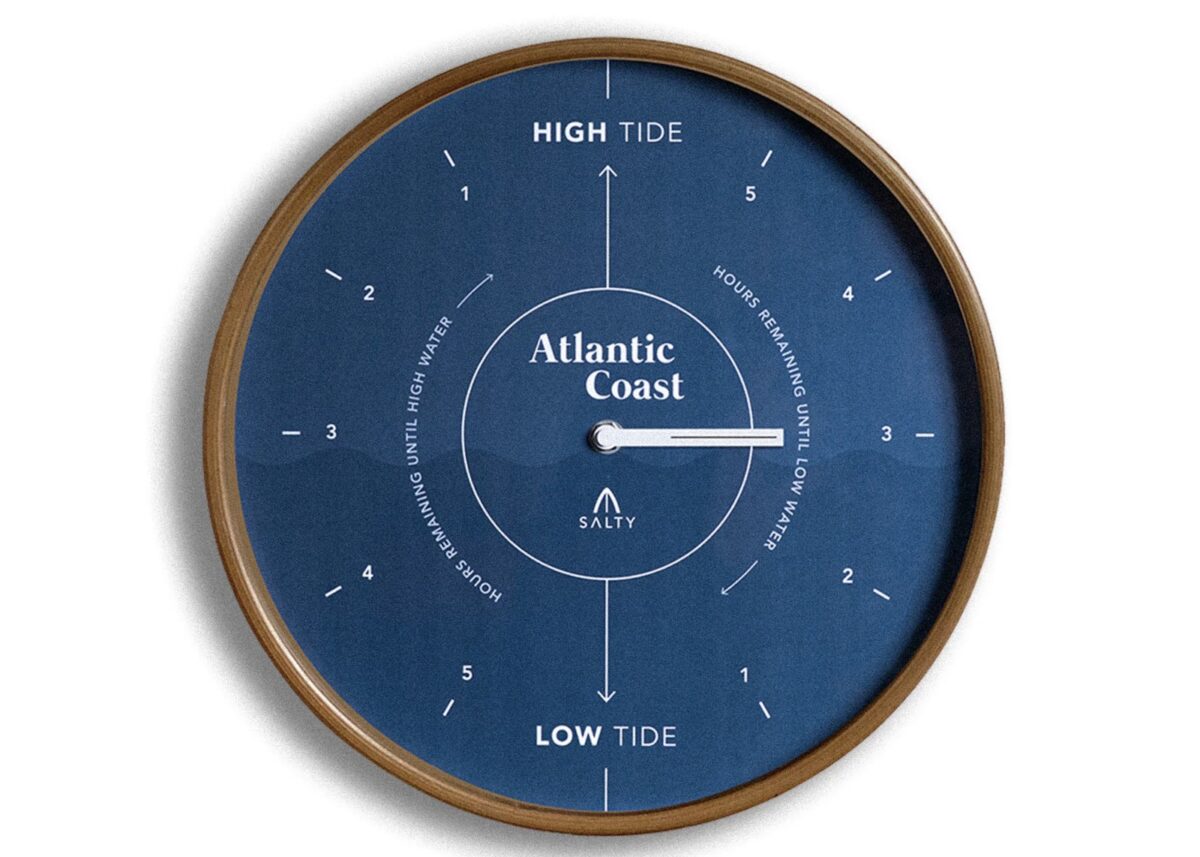

Tides

The ebb and flow of the ocean comes around about twice a day.

- High tide occurs when the sea level rises to its peak, and waves can break closer to shore.

- Low tide occurs when the sea level reaches its lowest point, and waves can break further from shore.

The tides have several effects on a given surf break. Perhaps one of the most dramatic effects caused by the shifting tides occurs at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach. Literal billions of gallons of water can flow in and out of the Bay as it passes under the Golden Gate Bridge. When the tide flows out, it drags the water along Ocean Beach and creates a powerful south current. When the tide floods, it brings water in and creates a powerful north current.

All this moving water constantly shifts the sandbars, making certain streets the hot spot for a given swell at San Francisco’s dynamic beach break.

Tides also impact wave quality. As with many of these factors, the behavior of the waves tend to be spot dependent. For example, low tide can produce more hollow waves at Ocean Beach, while high tide can produce more shoulders. That’s why OB is best for shortboarding at a low(ish) tide.

But should you travel a few miles down the coast to some of the breaks in Half Moon Bay, you’d find that low tide can expose the reef/rocks, making it dangerous to surf. Instead, these breaks perform better on a mid-to-high rising tide.

Wave Phenomena

Waves behave in funky ways. Here’s a short list of the oceanic occurrences you’ll encounter.

- Barrells, kegs, tubes, shacks, or pits are the holy grail of surfing. It is the cylindrical, hollow portion of a breaking wave that skilled surfers slot themselves into. A moment in this green room equals an eternity of bliss.

- Backwash happens when a surge of white water rushes back towards the surf. You can run and jump from the beach and ride it into a wave to essentially skimboard on your surfboard. Watch Italo Ferreira or Jamie O’Brien for a how-to.

- Burgers, or mushburgers, are the “lemon cars” of surfing. It is a defective, crumbly, soft wave that’s not fit for surfing. Some breaks are described as burgers when they are rideable, but not in the lens of performance surfing. “Main Break Margaret River is a total burger right now, why don’t they move the contest to The Box.”

- Closeouts happen when the wave breaks at once in a straight line parallel to the beach. It does not peel or create a face. However, closeouts with a slight angle produce the most dramatic barrel riding with swift and late exits.

- Double-ups are the result of two waves meeting. In an instant, the wave will thrust upwards and double in height. If you see a wave pop up on the outside — but not quite break — odds are it can result in a double up on the inside.

- Reforms are recycled waves. A wave may break on the outside, and still have enough white water energy to break again on the inside. See the Huntington Hop for evidence. However, reforms are the stomping ground from which all beginners emerge, and on a longer board reforms can bring back the nostalgia of learning to surf. Respect your roots.

- Rip-bowls are like Tinder hookups: fun while it lasts, but impossible to maintain a long-term relationship. Rip-bowls occur when the rip current water flow makes a channel near a sandbar. The wave creates a conveyor belt system where you surf to the channel, head back to the bank, and repeat. If you drift too far up the bank, the rip will carry you off.

Novelty Waves

When you’re tired of seeing perfect surf, novelty waves will psych you up and bring back that go-juice you need to get back in the water. Novelty waves have some X-factor that makes what would be a no-go wave a go-to spot.

The most famous novelty waves in the world are probably San Francisco’s Fort Point — surf under the Golden Gate Bridge — or The Wedge — a hulking shorey that fills your dental cavities with Newport’s finest sand.

- Tanker waves like those made famous in Texas are the result of large ships displacing water near a shipping channel. The result can produce very long rides.

- Lakes can produce storm surges. A man recently surfed Lake Tahoe in California when an atmospheric river slammed the area.

- Riverbreaks like those as Waimea occurs when fast moving water from a river flows over a contour such as the sand. Riverbreaks occur by the beach and also inland, like those famous ones found around Oregon.

- Pool$ are artificial wave pools that can either be standing — like the ones on cruises and water parks — or peeling waves — like the air factory in Waco. Bring your wallet.

- Wedges are the jacked up trucks of surfing. A wave can refract off something (like The Wedge’s jetty or Nazaré’s canyon) and meet up with another wave, creating a souped up double-up.

Conclusion be damned, there’s a lot of factors that make the surf the surf. But words are just words, and neither pictures nor videos can suffice. You need to feel these things for yourself. A day in the water — even if it’s raining, onshore, and 1-foot — will give you more experience than a 1,000 words, instagram pictures, or surf clips can give you…

…unless we’re talking The Raglan Surf Report, those videos are worth something.