John Milius trades Hollywood surf movie stinker Big Wednesday for Close Encounters of the First Kind and Star Wars!

Greg MacGillivray was 14 in 1960, the son of a Corona Beach lifeguard, small and pretty (his older sister was Miss Newport Beach) and absolutely relentless at whatever he put his mind to: paper route, math class, Boy Scouts—or, by 8th grade, making a surf movie.

Nobody saw Greg coming. He looked like a kid dressed up for Halloween as a surf movie-maker. He was almost invisible.

MacGillivray’s other superpower was that he could not be rushed.

Miss the deadline if you have to, but do the job right.

Greg later said he spent all his money (and borrowed from dad as well) and 90% of his free time on A Cool Wave of Color, his debut film, which took five years to make. He did the poster art. He painstakingly crafted little interstitial stop-motion animated graphics, which flash by onscreen in just a few seconds but really light the movie up.

Cool Wave debuted midway through MacGillivray’s freshman year at UC Santa Barbara. It screened a few times at various local Elks Lodges and high school auditoriums, and that was enough to earn a mostly-good review in SURFER.

“Cool Wave of Color shows blessed signs of creativity, [and] a musical score fitting to California waves.” (The criticism came near the end of the review, and was a small but literal kick to the nuts: “Greg is a young man and has a high-pitched voice.”)

Most of this I learned from MacGillivray’s new book, Five Hundred Summer Stories—the title is a riff on Five Summer Stories, Greg’s best-known surf movie, made with partner Jim Freeman.

Two other parts of the book caught my attention.

First, in the Fall of 1964 MacGillivray gassed up his new white-on-white Ford Econoline van—and again, the ambition and drive cannot be overstated; Greg’s work ethic is two-parts inspiring and one-part grotesque and while I’ve never met MacGillivray face-to-face he is in my Spirit Animal starting-five—and set out on a 6,300-mile coast-to-coast Cool Wave tour in which the film played at three locations.

Three.

A pair of shows at the North Hollywood Women’s Club, another in Daytona Beach, another in Virginia Beach. Driving cross-country and back for four shows seems insane.

But no, just the opposite. The whole point, as Greg well knew, was not to turn a profit, but to get out there and be seen, build momentum, gather experience—and the experiences came one after the other, big and small, high and low.

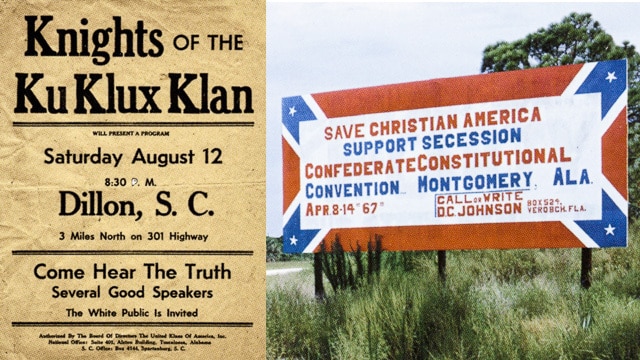

Driving through Alabama, just a few weeks after 30-plus black men, women, and children were hospitalized after being beaten and gassed during a peaceful march in Tuscaloosa, Greg grabbed a KKK rally poster from a telephone pole as a memento and was escorted out of town by a group of locals in a gun-racked pickup. Later, in a side trip to Manhattan, he visited MoMA and splurged on a Central Park carriage ride for his wife-to-be. MacGillivray loved surfing but also loved new experiences of any kind.

He was never not learning, always pushing forward.

The other thing: Greg headed up the second unit on the Big Wednesday shoot, and his description of that episode in Five Hundred Summer Stories reminded me yet again of that film’s humiliating public debut and its otherworldly rehabilitation.

Sharpen those knives, folks.

If you’ve been with me here awhile you know that time and tide have not mellowed my view of Big Wednesday, which was directed by John Milius and released in 1978 by Warner Brothers.

I first spaghetti-whipped it here, and did it again here. I make an exception for Gary Busey, who singled-handedly carries the first reel of Big Wednesday, and I also have a soft spot for Bear, the fallen shaper whose “lemon next to the pie” quote is sad and poignant while at the same time, and not intentionally, the movie’s comic highpoint.

But I stand by the idea that the Big Wednesday bad-review dogpile—read the Times takedown here and the Surfing magazine review here—was totally deserved, and that Big Wednesday getting unceremoniously yanked from theaters after a week or two was a mercy to all involved.

And you know who agrees with those dogpiling reviewers, according to MacGillivray’s book? John Milius himself, who called Greg personally to apologize for the film and to say that he “let everybody down.”

Except Milius, of course, got the last laugh—many laughs in fact.

Big Wednesday found new life in the 1980s as a video-rental favorite and then found a place into the Baby Boomer treasure chest of once-scorned-now-sacred cultural artifacts, right next to the Monkees and Ronald Reagan.

But before that happened, there was a second and maybe more astounding Big Wednesday consolation prize, which I believe is a one-off in the history of Hollywood. MacGillivray tells the story:

I began making day trips to Milius’ office at Warner Bros. In the adjoining office sat Steven Spielberg [who was] working with Milius, writing and prepping the comedy feature “1941.” The unions still had incredible control over Hollywood, but Spielberg, Milius, and their friend George Lucas were challenging the status quo with enormously profitable films. One day the three of them were at John’s office and we were all joking around about filmmaking. I would later learn that they had each agreed to share some of the profits from the three personal projects they each had in production. Incredibly, Lucas’ film was Star Wars and Spielberg’s film was Close Encounters of the Third Kind. John’s film was Big Wednesday. [Each filmmaker] gave each away two points from the net profits they owned in their own creations [to the other two filmmakers]. This was their way to show the old-time studio bosses that a new era had begun of youthful, creative collaboration.

“The deal worked out better for some than others,” Spielberg later told MacGillivray, laughing at the lost millions of dollars. “We haven’t repeated the practice.”

(You like this? Matt Warshaw delivers a surf essay every Sunday, PST. All of ’em a pleasure to read. Maybe time to subscribe to Warshaw’s Encyclopedia of Surfing, yeah? Three bucks a month.)