“It’s no conspiracy, it’s just the way things are. Whether conscious or not, we’re never subjective when it comes to emotions.”

Martin McDonagh’s tragicomedy The Banshees Of Inisherin has been an unlikely tour de force in the film world. Despite multiple awards and gushing accolades, it’s a film with an understated, or even uncertain, appeal. Set on a fictional Irish island, the film is about the breakdown of a lifelong friendship between two men for little reason other than one gets fed up of the other.

For me, it was overrated, but it does contain some ideas I’ve found myself returning to time and again. Today, as the Rip Curl Pro from Bells Beach played out in weak windswell and confusing, controversial scores, I found myself thinking of it often.

In the film, during a confrontation in the pub, a desperate Padraic berates his estranged friend, Colm, for ending their friendship so abruptly. “You used to be nice!’, he exclaims.

“Ah well, I suppose niceness just doesn’t last.”, replies Colm. “Do you know who we remember for being nice?”, he retorts. “Absolutely no-one.”

This idea has haunted me.

I thought of it in the very first heat of today as Gabriel Medina lost to Ethan Ewing. In the booth, pundits Blakey and Lovett discussed the fact that Medina was more approachable and less intimidating these days, and questioned whether he’d lost some of his edge as a result.

The conventional wisdom in sport at the highest level is that niceness gets you nowhere. All the greats exist on a scale from prickly to outright cunt. Tiger Woods, Michael Jordan, Lionel Messi, even our own Kelly Slater. To be the best you must forgo politeness, family and friends, a balanced lifestyle. If you want to win, you need a bit of mongrel in you, so goes Australian vernacular.

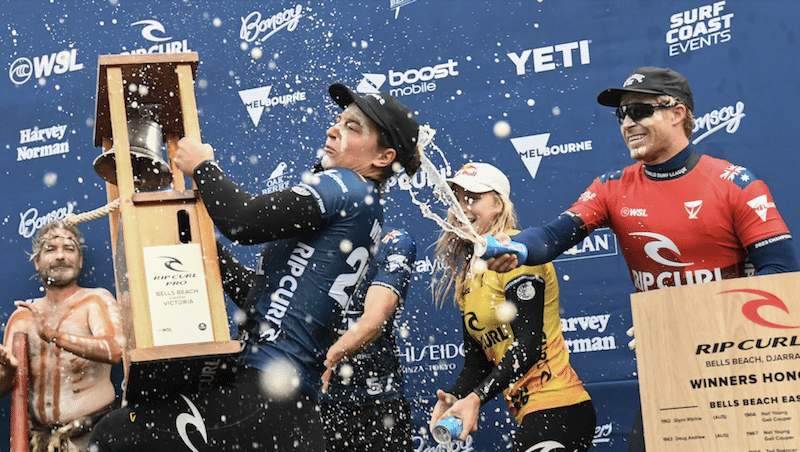

Yet today at Bells Beach, this wisdom was challenged. Finalists Ryan Callinan and Ethan Ewing are considered two of our sport’s “nice guys”. Today they seemed rewarded for this niceness, eventual winner Ewing greatest of all.

When conditions are solid or consequential, scores are often unequivocal. On days like today, the field is flattened. Perhaps niceness gets overscored. Perhaps the man is scored more than the surfing.

From the beginning it was clear that airs would not be rewarded. Medina was the unfortunate guinea pig who elicited this unspoken decision from the judges, believing aerial manoeuvres in mediocre conditions could be a point of difference. Their preference was for linking turns. If only Medina had known.

Any surfer on Tour, or any solid intermediate, could string a few turns together on waves like today. Only a handful could manufacture the speed and technique for full rotations. It’s worth questioning why they weren’t rewarded.

Filipe Toledo had cause to question things. It was a twitchy, wiggly sort of day for most as they hunted speed, but less so for Toledo who has striking velocity on days like this. And he knows it. He knows that in marginal conditions, barring judging discrepancies or acts of god, no-one can touch him.

Which is why, when Jackson Baker dropped a nine point ride at the close of their quarter final, seeming to turn the heat at the death, Filipe fell back to his native tongue as he ranted and raved on the stairs. It took no interpreter to decipher this language of passion. But just to clarify, his face loomed into the nearby camera lens. “Nine? Nine!?”, he exclaimed.

He’d seen Baker’s wave from the back, of course. Understandably, given he saw little of Baker’s fins, he must have wondered what sorcery was conducted on the face of the wave to warrant that score. Having seen it now, he might be less aggrieved, as it was surely a well-surfed wave. Whether it was worth a nine is up for debate.

In conditions like this, an opponent like Baker must seem like a walkthrough for Toledo, and his reaction certainly suggested as much. It was the most animated we’ve seen him in some time. Throughout his whole world title run he seemed almost demure. Perhaps even nice.

The tension was palpable as we waited for Filipe’s final score. He needed a 6.91. Eventually the judges awarded him a flat seven.

Once again, he grabbed the nearest camera, thrusting his face into our screens. “Keep trying! Keep trying!”, he spat. The niceness of last year had been shattered, by Jackson Baker, of all people. The camera cut to a break (of course it did) just as Toledo was having his shoulders massaged by a countryman in an effort to calm him down. He’d won, but he was far from happy.

“There’s scoring that I don’t understand sometimes”, he said to Rosie. How might he deal with Ewing in the semi, given he’s been surfing so well, Hodge asked next in a manner that seemed uncharacteristically provocative. “I’ve been surfing good too”, Filipe snapped back. “Bigger scores, if they allow me to”.

But if judge’s good graces awarded bigger scores last year on account of niceness, today he would be punished for his vitriol.

He seemed the dominant surfer in his semi-final bout with Ewing. Riding eight waves over the course of the heat whilst Ewing sat dormant, Toledo racked up five scores that might be keepers in these conditions, and held a comfortable lead with a pair of sevens. His surfing looked sparky and agile. He had the ability to spin above the lip, an advantage over Ewing much like Medina, yet similarly unrewarded.

Ewing’s surfing is undoubtedly silkier than Toledo’s, and there’s little to separate the men in terms of flat out speed, but Filipe’s is higher risk, more dynamic and more radical. That’s just the truth.

Ethan caught only three waves. The definitive score, his 8.43 for his last wave, was ludicrous. It’s as blatant a judging cock-up as we’ve seen all year. Richie Lovett knew it. Not as good as Toledo’s 7.17 he stated. “Gets a bit sleepy…little foam climb”, he said in his breakdown. Then the score came in and in typical WSL fashion no-one voiced their dissent.

Watching it back now, I still can’t see the score. It was nice surfing, but that’s about it. By Ewing’s standards it looked lackadaisical. The fact that Toledo can bust a full rotation above the lip on his first turn, before finishing with a couple more, and still be scored a point-and-a-half less is scandalous.

For me, Ewing was similarly overscored in his quarter final match with McGillivray. See Ethan’s 6.10 (speedy foam climb to mushy end section layback) vs Matt’s 6.17 (two solid turns, one with fins out, ending with a full rotation and clean landing) as evidence.

On the other side of the draw Ryan Callinan progressed via a tight win over Colapinto in the quarter, and a convincing one over Florence in the semi. Two solid opponents downed by Callinan’s backhand which lent a smooth approach to the weak waves.

Colapinto was superb throughout the contest, particularly in his grudge match against Kanoa, and he looked a certainty to be in the final. I’m conscious I haven’t mentioned Florence’s name once in three reports, despite the fact he’s reached the semi. The truth is I’m not seeing a lot to be excited about in John’s surfing. Wake us both up when the waves get good.

Ewing went on to win the battle of the good guys in an uneventful final. Both men vault up the overall leaderboard, Ewing into fourth, Callinan into sixth.

Pundits are in love with Ethan Ewing. Everyone is. I see the appeal, in surfing and character. Because he’s quiet, we assume he’s nice. We look at his interviews as humble rather than bland. We shower him with compliments, as we often do to talented people who don’t seek the limelight. And his surfing encapsulates everything we value, commitment without showiness, effortless style and flow, a smooth aggressiveness. No claims, no over-exuberance.

But it would be remiss of me as a reporter, and all of us as fans, not to point out the potential lack of objectivity in days like today, and the ways in which we might be influenced by emotion, empathy and the cult of popular opinion.

You might watch The Banshees Of Inisherin because it’s won so many awards, or because people have talked about it. You might even watch it because I’ve mentioned it now. Perhaps you’ll get it, perhaps you won’t, but regardless of what you really think, some of you will pretend to love it, simply because so many others do. Or you’ll look harder for the appeal, convincing yourself you really do.

When scoring is subjective, like film awards or professional surfing, opinions create waves of support that build exponentially. It makes sense. We’re human beings, communal animals who feel strengthened by our connections to others. Shared views make us feel validated.

Ethan Ewing’s surfing is extremely pleasing to the eye, as is his demeanour. He’s probably a nice guy. All of this is important. There’s no secret judging mandate to juice his scores, but human beings collude silently in matters of the heart.

And we exist on the power of stories, a fact not lost on the WSL. On an emotional level, you’ll find no detractors to Ewing’s victory at Bells. After all, it’s the sixtieth version of this prestigious competition, and not only were two young Australians in the final, both of whom tragically lost their parents to cancer at a young age, but it’s forty years to the day since Ewing’s mum, Helen Lambert, rang the bell herself.

It’s no conspiracy, it’s just the way things are. Whether conscious or not, we’re never subjective when it comes to emotions. And maybe no-one remembers niceness, but they do remember wins. The names on the Bells stairs come without asterisks. Ethan Ewing’s will be there beside his mum’s for evermore.

Objectivity be dammed, that’s a nice story.