Toledo now faces the unthinkable, requiring good

results in real ocean waves that may be large.

“Look at this incredible facility,” chirruped Joe

Turpel. “Look how far we’ve come.”

A drone hummed through the Arabian sky. It conveyed a streak of

gleaming blue and astroturf green smeared amidst flat, arid

sandscape.

On the horizon, buildings with indeterminable purpose gleamed

like sentries.

Minitrue. Miniluv. Minipax. Miniplenty.

It was a phallic skyline. One building is an inexplicable red in

the low desert sun. Sex toys for androids.

There is no undulation in this landscape. No geological

processes to shape and carve. There is only the hubristically

straight lines and fantasies of man and machine.

Look how far we’ve gone, Joe, I muttered quietly to myself.

Look how far we’ve gone.

“Bringing this really cool rush of surfing to another part of

the world,” Joe returned.

“It’s always pumping, always perfect,” he continued in wilful

blindness.

But it wasn’t. It was onshore. Man had harnessed waves but been

smote by wind.

Regardless of how you feel about wavepools on a moral or

aesthetic level, you can’t deny a rubbernecking curiosity at the

absurdity of it all.

For all the WSL’s kelp farming, virtue-signaling, mother

naturefelching, sustainable wokeness, here they are, in the Middle

East, eons away from everything that is real, from all that surfing

has been and done.

And everyone capitulates. There are

no Tom Carrolls in 2025.

But it would take some thick moral fibres for surfers to stand

against perfect waves. Regardless of your bent for social justice

or anything else, in the face of perfect waves (offered freely by

your employer, with a side serving of six star hospitality) your

sense of morality would fold like the Burj Khalifa made of

cards.

For the surf fan, there is multi-layered interest in this

competition. Alongside morbid curiosity in the inevitable downfall

of man, one might find interest in how surfers respond to

scrutiny.

In the pool, technical skill and composure is laid bare. There

is nowhere to hide.

What we find, somewhat predictably, is that the field of

watchable competitors is scythed down. Look no further than the

perennial contenders, all victorious in their opening round heats:

Jack Robinson, Ethan Ewing, Filipe Toledo, Yago Dora, Griffin

Colapinto, Italo Ferreira, Jordy Smith.

Really, these contests are a gambler’s dream. (Though not this

one, owing to exclusion from bookmaker of choice.)

But what the competition has lacked so far, aside from the

promised perfect waves, is any discernible tension.

Crowds are non-existent, despite the quite reasonable fees on

Ticketmaster of twenty-five to forty of your Aussie dollars.

Heats took far too long to complete. Many were over with several

waves left to surf, the winner already established.

One left and one right each should be sufficient for a wavepool

competition. Cut the time. Crank the pressure.

Additionally, and somewhat bizarrely, there was no scoreboard on

screen, and therefore no way of knowing what a competitor had

already scored or what he might need unless the pundits told

us.

Judges’ scores appeared from the digital ether fully formed.

There was no waiting for one or two scores to drop. And there was

even less sense than usual that human beings presided over the

process.

It had all the tension of a dressage event. Watery prancings

were punctuated by the occasional misstep, to muted

disappointment.

Despite this, the contrast in approaches of some surfers was

notable.

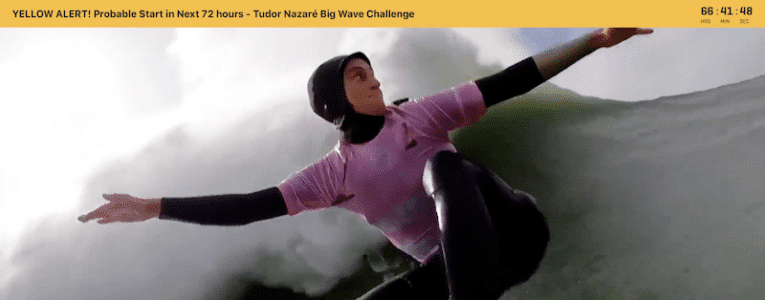

Italo Ferreira, the would-be world wavepool champ, a man whose

game was built for this, was typically jangling. “I would love to

have a close out on the end,” he chittered in his post-heat

interview. “So I can go a little higher.”

Filipe Toledo, quite understandably, was similarly overjoyed to

be back in his happy place. A safe haven of four-foot mechanical

waves. He was noticeably quicker and more precise than anyone else.

Up, down, up, down. Metronomic. He anatomises waves in pools with

the assuredness of a kestrel dissecting a vole.

By contrast, Jack Robinson approaches the pool with the languid

boredom of man for whom the predictability of waves presents little

challenge. He was like a stud in the Red Light District, perusing

easy game disinterestedly, before capitulating to his primal

instincts and getting stuck in nonetheless.

Some surfers attempted a different visual approach with board

colours, which I thought a savvy move to create separation in the

sameness. Barron Mamiya opted for lurid orange, but this did little

other than clashing with his yellow jersey. Yago Dora chose a flat

blue deck with lime green rails, and had greater success.

In terms of visual appeal, I’d been expecting a little more than

Lemoore, but it was much the same. The night surfing was a cool

gimmick. But it didn’t last long. Eventually I zoned out and went

full meta, thinking about thinking about surfing.

Until I was accosted by Miggy Pupo ripping the bag out of his

lefthander under the lights. Worth watching for his Marzo-esque

nosepick.

Really, the whole thing is about optics. And it’s hard to see

ourselves as others see us.

Banality was momentarily broken, along with Toledo’s fins, in

his round of 16 heat with Kanoa Igarashi. This marquee match up

between two of the most likeable men on Tour had been dominated by

Igarashi from the off, spurred on by the straight-talk of coach

Jake Paterson.

Back against the wall, Toledo narrowed his beady eyes and

attacked the right hander. But something was off. Mistiming his

first couple of turns, he straightened his back and cruised through

the middle section of the wave, before regaining consciousness and

launching a huge alley-oop. But god had not forgiven him for the

lapse. In his next cutback, he ran over a water photographer,

breaking two fins. Whilst the poor lensman tried to crawl through

the wire fence and commit hari kari in front of the wavetrain,

Filipe slapped his board, threw a rash vest and used big sweary

words. Lots of gesturing from hangers on indicated a desire for Pip

to go again, but Renato Hickel deemed the scoring potential at that

stage to have been insufficient. No more gravy for Pip.

Toledo now faces the unthinkable, requiring good results in real

ocean waves that may be large.

My eight year old, completely apathetic to surfing, was

transfixed by the pool.

“Come and see the cool surfing stunts!” he called excitedly

through to his younger brother. He was a slave to the end section.

The predictability of it all captivated him.

“Oh no, not the sea!” he exclaimed in the breaks between heats

as we were shown drone shots of Bells and Peniche.

Oh no. Not the sea.

Look how far we’ve come.