“Curren was the last surviving member of the four men who, in the 1950s, more or less invented big-wave surfing.”

Big-wave surfer and boardmaker Pat Curren died last Sunday at age 90.

Here it is a week later, no decent obit has yet surfaced, and I’ve got six phone calls out trying to find out the simplest of facts, like where he died, Idaho or Utah or California or somewhere else, but no luck there either, so the Pat Curren mystique continues unto death.

He always kept us at a distance. The quiet checkout was all but guaranteed. Lots of social media tributes, though, with many comments having to do not with Pat’s courage or shaping skill—plenty of those, too—but the gold-standard level of cool he brought to the sport.

Curren never sold out, did everything on his own terms, let his actions speak, walked away at the right time, and etc.

Who knows what Curren himself would have thought of all this. He gave up a centerstage position in surfing in the early 1960s and did little or nothing over the decades to publically shape the narrative one way or the other, apart from staying out of the spotlight for decades at a stretch.

On those rare occasions when he stepped forward, he wore his legend lightly.

“You see this sign, ‘Welcome Surf Pioneers’,” Curren said in 1991 about the celebratory events that were common around that time, when most of the first-gen surf stars were still alive, “you get a couple of drinks, start moving down the line, seeing some of the guys, then they kick you out at 9:30.”

Curren was the last surviving member of the four men who, in the 1950s, more or less invented big-wave surfing. Two—Greg Noll and Buzzy Trent—were loud and aggressive and larger than life, and the Marvel-like surf-action figures they created, with their jailhouse trunks and grimly presented Sgt Rock biceps and headline-ready quotes about “increments of fear” and “the big damn terrorizing wave,” have kept us thrilled and entertained for 60-plus years now. The other two—Curren and George Downing—went the other way and didn’t work for our attention at all. They played the big-wave experience down, and by doing so created a second and equally compelling way to set themselves above and apart.

Noll and Trent were hot, in the exaggerated show-biz sense of the word. Downing and Curren were cool. George came first, and contributed more to the sport. But Curren, in the end, may have chilled his way to the very top of the big-wave pantheon.

From History of Surfing:

Curren was the slouching near-mute apotheosis of surf-cool: draining an afternoon beer, flicking a cigarette butt to the side, then taking down Malibu golden boy Tommy Zahn in a paddle race; flying to Hawaii one season with no luggage save a ten-pound sack of flour for making tortillas; sailing the three-thousand-mile Great Circle route from Honolulu to Los Angeles on a 64-foot cutter and posing for a photo en route, bearded and watch-capped, a huge Havana cigar jutting from a corner of his mouth, left hand on the wheel, right hand holding a shot glass of crème de menthe.

Cooler than all these things put together, Curren would invariably pick off and ride the biggest, thickest, meanest wave of the day. With Zen-like patience he’d sit on his board, alone, ten yards or so beyond anybody else, and wait an hour, two hours, three hours if necessary, for the grand-slam set wave. The ride itself was stripped down and fluid, as Curren went into a deep crouch, spread his arms like wings, and led with chest and long chin. Tearing across a huge wave face, in circumstances where other riders dropped automatically into a survival stance, Curren looked like an Art Deco hood ornament. “And he didn’t give a shit if anyone saw it or not,” fellow big-wave rider Peter Cole said. “The rest of us would run around, chasing photographers, ‘Did you get the shot? Huh? Did you?’ While Pat would just grab the wave of the day, walk up the beach, and vanish.”

Like everyone else, I’m enraptured by the photos and stories that together form the Pat Curren legend. But experience has shown me that legend, as a rule, is almost always a portal to a more interesting and complicated and human story, and Curren is a prime example of what I’m talking about.

The celebrated and ineffable cool he brought to the table—the silence, the independence, the not giving a shit—very much cuts both ways.

The cool is real.

But it unmade him as much as it made him, and to gain some measure of what I’m talking about you have to read “Father, Son, Holy Spirit,” Bruce Jenkin’s deep-dive and slightly schizophrenic 1995 SURFER feature, wherein Curren is directly and repeatedly lauded for all that I’ve mentioned above, but also revealed as a solitary figure sitting in front of a beat-down trailer in Baja, 14 years past when he left his wife and three children—high school sophomore Tom Curren was the oldest—in order live alone and off the grid, supporting himself with one-off construction jobs and by making the occasional balsa-replica big-wave gun for board collectors.

Families fall apart, and who knows what kind of strife and pressure and anguish was at play here, and I have little doubt that in Pat’s mind leaving America was a least-worst option.

But let’s not parse too finely. This is abandonment, simple enough.

Curren, in 1980, wasn’t vanishing from the cameras or the surf press or the guys on the beach or whatever. He vanished from his own kids.

Some of the damage was later repaired.

In 1985, Tom visited Pat in Costa Rica. Younger brother Joe drove or flew down semi-regularly to see Pat in Baja.

In 2000, all three visited France and Ireland—their first and only trip together.

But everybody involved was damaged to some degree when Pat dropped out. Fred Van Dyke tells Bruce Jenkins that Curren is “sort of a Hemingway character, living on his own terms.”

And Greg Noll follows up by saying it is “so bitchin’ [that Pat] is doing the same shit he found enjoyable back then [in the 1950s].”

But this is good-buddy happy talk, and in fact we’re light-years removed from cool and into something reduced and broken and melancholy.

Bringing us to Jeanine Curren. Pat’s former wife, and probably the last person Pat would have us look to at this or any other point. Jeanine is portrayed in this 1985 Sports Illustrated article as a busybody with regard to her soon-to-be-world-champion son, Tommy—and she was indeed a busybody, but she also deserves full credit for keeping him from going off the rails before and after Pat left the family—and Pat Curren refused to talk about her with Jenkins.

Jeanine, on the other hand, was open to talking about Pat, and it turns out that if we’re looking to reconcile the quiet North Shore big-wave legend with the self-exiled figure Jenkins found at the tip of Baja, Jeanine is the right person, probably the only person, for the job.

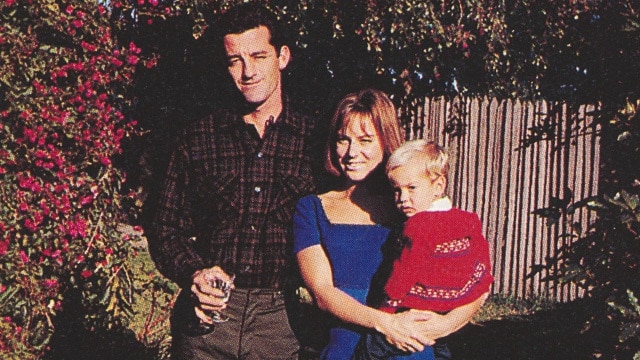

She tells Jenkins that her honeymoon winter with Pat on the North Shore in 1961 was less than romantic, with surfers showing up unannounced with cases of beer, ready to settle in for the afternoon, and a shaping rack in the kitchen, where the “butter tasted like resin.”

She tells Jenkins that Pat’s parents lived in San Diego and that right before Tom was born, Pat’s mother, a smoker, somehow lit the house on fire one night and Pat’s father died as a result. “Things were never the same” in the Curren family after that.

Finally, she tells Bruce that Tom, by age 10, was out of control, getting high and running away, and that Pat simply could not handle it, saw his life as “an impossible situation, [so] he made a toolbox, put his tools in it and said goodbye.”

You could justifiably build and maintain a lifelong anger from all of that. But Jeanine, instead, is beyond it, at peace, reconciled, which allows her to be not just forgiving but gracious. She deserves the last word on Pat Curren.

He was a good man, a likable man. He was discouraged and didn’t know what else to do, so he went out in the wilderness. I don’t hold it against him. I’ve forgiven him totally and wish him only the best. People say, ‘He’s a survivalist; he’s a real man’s man.’ That’s a bunch of BS. Pat is humorous, he loves people. He had an amazing way of connecting with people. He could be so intimidating with his quietness, [but] everywhere he went, he had friends.

PS: Pat Curren married again, and again became a father, and moved back to America, but I know almost nothing about that period of his life except that two years ago the family was temporarily living in a trailer parked off PCH in San Diego County, and that a GoFundMe on his behalf raised over 70K.

PPS: Mike Curren, Pat’s older brother and the inventor of Over the Line, a cross between baseball and a July 4th beach party, died earlier this month, at age 92. Read the obit here. No mention of Pat Curren.

(You like this? Matt Warshaw delivers a sassy surf essay every Sunday, PST. All of ’em a pleasure to read. Maybe time to subscribe to Warshaw’s Encyclopedia of Surfing, yeah? Three bucks a month.)