“He was the best shaper. First guy to shape it, first guy to ride it. He was so respected, he had a cult following. He was a guru.”

The most beautiful surfboard I have ever seen was shaped by Pat Curren. It was in Jack Reeves old shop tucked behind a snarl of Keawe bush at Don Bachman’s place across the street from Rockies Mauka side of Kam Highway.

Along with Curren’s longtime surfing and shaping partner Mike Diffenderfer, Jack was restoring this elegant balsa broadsword for Ricardo Pomar, who had recently acquired this treasure through some sort of clandestine negotiation.

Before finding its way to Jack’s shop, the Curren gun had been hanging behind a dingy bar in Town, a place called “Nicks” near Waikiki, just off Kalakaua Avenue.

It belonged to the barkeep, a local Hawaiian named Freddy Noa. Reportedly, Noa had been a decent surfer back in the day (1950s) as well as an associate of Pat Curren. Noa somehow ended up with this masterpiece in the 1960s.

Thereabouts 1988-89 or so, he was looking to sell the board to the highest bidder. Flippy Hoffman (also a friend and contemporary of Curren) bid $2000, but he never paid up. That’s when Ricardo stepped in and offered $2500 in cash, which, at the time, Noa was happy to take.

After having Jack and Diff restore the board to original, pristine condition and admiring it in his possession for the next 30 years or so, Pomar eventually sold “Stradivarius” (as it was called) for almost ten times what he paid for it — much to Noa’s chagrin, who had tried to buy it back from Ricardo more than once. So it goes.

At the time, probably 1990 or so, I was living at V-Land on Kaunala Street in a house full of heavy big-wave riders with their Brewer and Owl pintails hanging in the rafters, otherwise strewn around the house or in the living room standing against the walls, and out in the garage. I had a few Owls myself at this point and was well-accustomed to the omnipresence and gravitas of the “finest, hand-crafted precision surfboards in the world” (quoting the Brewer-Chapman “Top Gun” logo). At the tender age of 21, I had already become a surfboard connoisseur.

Some years later, in 2002, I had the opportunity to meet Pat Curren. It was late Spring, probably April, and I was out alone surfing Sunset Point, just down the street (Huelo) from where I live. The waves were small and clean, a little West swell refracted perfectly off the Boneyard into crisp, bowling runners across the reef.

I love days like that. I was riding one of my three-stringer 11’ single-fin pintail semi-guns shaped by Owl (a modern interpretation of the original “Pipeliners” designed and shaped by Brewer in the mid-‘60s for guys like Pat’s Windansea bud Butch Van Artsdalen). Cruise control in full forward trim. As I sat there by myself waiting for another set, I spotted someone walking down the path at the public beach access to what is called “Mother’s Beach.”

In some way, I knew immediately — instinctively I suppose — that the figure I observed slowly making his way to the shoreline, a longboard under his arm, almost a hundred yards away, was Pat Curren. No lie. I knew it was him. I was stunned, almost took my breath away. I’d actually seen him a few years before (1999) when he was on the North Shore for a minute. At that time, he was at the Bay watching his son, the three-time world champion Tom Curren, ride a beautiful morning of fifteen-to-twenty-foot waves on a replica gun he had shaped for his son Tom.

Tom and I spoke in the water that day and I checked out his board (it was beautiful). Tom was charging, of course, surfing it well. When I came in and walked by the lifeguard tower on my way to the showers, I saw Pat Curren standing there alone. I didn’t say anything. I was in awe.

So, I guess I must have intuitively recognized him from the initial passing encounter. That day in 2002, he looked old, though, and tired; older than the 70 years I suppose he was (doing the math in my head), as well as a little awkward, kind of off balance, as one who hasn’t paddled a board in a while often appears. I just sat there and observed, although I didn’t look too closely out of respect and deference.

Still, it was just him and me out there. I was stoked! Curren paddled right up next to me. Didn’t say a word. Neither did I. A set approached. He laid down and began to paddle for the wave.

Curren caught the wave. But, as I remember, he didn’t (couldn’t?) stand up. He just sort-of belly rode the wave until it faded out on the inside in the channel. I thought to myself: “There but by the grace of God and time go I” – goes all of us if we make it that far in life. Even and especially the best grow old, weary, and lose it, sooner or later.

I recalled Ricky Grigg telling me a how he regretted losing his timing and balance, the ability to leap to his feet (in his sixties). Peter Cole often recited the adage: “We start off as kooks and we end up kooks.”

To be sure, however, Pat Curren is no kook.

I caught the next wave, trimmed across the bowl, and kicked out, gliding next to him. We paddled back out together, me just a little behind him, again out of respect for a man I revered as a demigod. No words. Not yet. Once we returned to the lineup zone, we both sat up on our boards and Curren said casually: “Nice board you got there.”

I smiled and said “Thank you.” He asked who shaped it and I told him that Owl Chapman did. He smiled and said: “I thought it was a Brewer,” adding graciously that “My name’s Pat.”

We talked story for a bit. He told me he had been in Mexico and was in town to say goodbye to Mike Diffenderfer, his old friend from Windansea and early North Shore days.

Of course, I thought, knowing that Diff was terminally ill (with brain cancer) and in hospice down the road in Waialee at the Crawford’s Convalescent Home. A melancholy moment, signalling the end of an era.

We traded off a few more mini-waves, Pat belly-riding and seeming to enjoy himself. Then he went in and disappeared up the path. Gone as quickly and quietly as he had appeared. I never saw him again.

“Part of his pure quality,” Ricky Grigg recalled around this time “was his inability to compromise with society, which was why he came to Hawaii in the first place. The fact that he’s [living down] in Mexico, in that setting, is completely consistent with that attitude.”

Fred Van Dyke offered this insight:

“I’m not sure anyone really knew Pat, I don’t think anyone ever penetrated his depth. And that was sort of his charm. He was quiet, strong and silent, sort of a John Wayne type. . . . The image I’ll always have is from Waimea one day in 25-foot surf. We’re all standing around, waxing our boards, and there’s Pat with a cigarette and a beer. He walks down to the shore, flips the beer over his head, kicks the cigarette into the ocean, paddles out and catches the wave of the day.”

That exquisite Curren javelin I saw in Jack’s shop back in 1990 was something to behold. Otherwise known as “Stradivarius” — an allusion to the rarefied violins prized for the highest quality construction and finest sound — the board was shaped sometime in the late ‘50s (’58? ’59?) from a beige balsa blank, ten feet six inches (10’6”) in length, composed of seven redwood stringers; a narrow tail pulled tight into a baby squash; super hard rails; a little roll in the belly near the nose flowed into a flat panel that ran into a relatively small fin that looked more like a rudder or keel (in stark contrast to the more modern broad-based, raked gun fin later developed and refined by Brewer, Jack, and Owl to which I’d become accustomed). At once exotic and erotic, this was an extremely sexy surfboard.

Indeed, this spear-like gun was an exceptional work of art, like a sculpture by Michelangelo. It wasn’t no wall-hanger judging by the dings and water damage. It was the original “Rhino Chaser,” an “Elephant Gun” (both terms coined by Curren’s loquacious peer, Buzzy Trent), a “Stradivarius” shaped and designed to catch and ride the best, largest, most challenging waves in the world at Waimea Bay. Moreover, this was, in fact, the first board to successfully ride the biggest, baddest waves in surfing.

Jack Reeve’s shop was and remains comparable to the Louvre, the Smithsonian, and the Museum of Modern Art all in one – or, alternatively, the workshop studio of Leonardo Da Vinci – when it comes to flawless surfboards. Ground Zero. The epicenter. Where it all comes together into the final, finished product. Only the finest specimens of the state of the art of shaping and glassing – Non Plus Ultra, or, as the Hawaiians say: No Ka Oi. Predominantly Brewers and Owls, balsa and foam masterworks (mostly Sunset and Waimea boards), including a few Diffenderfer wooden masterpieces, as well as a variety of finely tuned foils shaped by Pat Rawson and Chuck Andrus designed for the Pipeline Underground.

In this enchanted milieu, the board shaped by Pat Curren was outstanding. Owl pointed to it and said to me: “That’s where it all began.” The prototype for the modern big-wave gun.

Brewer said as much, too. Reflecting on his evolution into the greatest shaper of all time, RB gave unambiguous credit to Curren as being one of the “the greatest” influences on his shaping philosophy and practice back in the early 1960s, along with other notable innovators such as Joe Quigg, Bob Sheppard, and Diffenderfer, all of whom were in their prime as Richard “Dick” Brewer came into his own under the label Surfboards Hawaii, which he founded in Haleiwa in 1961.

Largely based on what he observed and learned from the Maestro Curren, Brewer completely revolutionized the design and shape of the modern big-wave gun.

In such regard, Brewer credited that “Curren was into hard rails and flat bottoms. Pat put as much flat bottom as he could into a board. [In 1960] he was in in his prime . . . Curren was the greatest. I took off from where he left off.”

I was enthralled as I ran my hand across the flat bottom, along the rail, felt the turn of the rail in the middle blend into a razor-sharp edge near the narrow squash tail. Not only did it look like it could catch and ride a giant wave, this board actually did catch and ride the biggest waves (then as now: 25’ plus) at Waimea Bay in the late 1950s and early 1960s, surfed masterfully by the man who shaped it: Patrick King Curren.

Peter Cole, one of the “Coast Haole” pioneers that first migrated to the North Shore and charged Sunset and Waimea along with Curren, stated plainly: “Pat was the master, the King of Waimea. To this day, I’ve never seen anybody get bigger, cleaner waves or ride them so well.”

Anna Trent (Buzzy’s daughter) corroborates Cole’s testimony: “Then, even by the standards of now, [Curren] surfed the Bay impeccably well. Some say the best.”

Top Gun. Non Plus Ultra.

Highest praise. The “King” indeed.

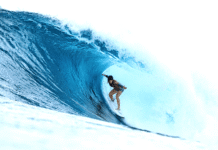

This isn’t nostalgic bluster or hyperbole. I’ve directly observed and surfed with the best big wave riders for the past four decades at The Bay and I can attest with confidence that the waves I’ve seen Curren ride in the old surf films alone (not to mention what I’ve been told by reliable authorities like Peter Cole, Ricky Grigg, and others who surfed with him) including all the photos and testimonials from other first-hand witnesses (etc.), Pat Curren rode as well (and big) as ANYBODY then or now — including this most recent Eddie Invitational (January 22, 2023) which was held in absolutely maxing 25’ plus epic Waimea with the best surfers: Luke Shepardson, Billy Kemper, Mark Healey, John Florence, Kai Lenny, and the rest.

What a name, too: Pat “King” Curren — one he lived up to. He was one of a kind. Singular. Born in 1932 in Carlsbad and raised in and around Mission Beach with two brothers, Curren described himself as “growing up bodysurfing and belly boarding in Mission Beach.”

When it came to board riding, he started in 1950, 18 years-old at Windansea, the archetypal La Jolla surf spot, known for its strong surf and idiosyncratic locals. “Nobody taught me to surf. Does anybody teach anybody? It’s kind of like learning how to ride a bike. Somebody gives you a push, then watches you crash into a pole.”

The laconic Curren was conditioned by a feral environment near the Mexican border in the raw, open-ocean waves of Windansea and the wild, lawless environs surrounding Tijuana.

In the post-war era, there was an uninhibited subculture of non-conformist Epicureans of a certain athletic (if also alcoholic) bent, those who lived close to nature, spontaneously, by their wits and handiwork, even artistry, rejecting the strictures of the Eisenhower Era; while the rest of an American herd dutifully complied with the homogenizing, self-limited prospects of the 1950s. Surfers in general, and Curren in particular, were Aquatic Bohemians, energetic, hedonistic rebels that aspired to a form of Eudaimonia (human flourishing) not seen or experienced since the Ancient Hawaiians. Along with other luminaries from the La Jolla Windansea crew (e.g., Mike Diffenderfer, Butch Van Artsdalen, Al Nelson, Wayne Land, Dave Cheney, Buzzy Bent, et al.), Curren was a unique exemplar of this dare-devil, seemingly reckless, rebellious spirit.

Soon after he started surfing, he began to build surfboards, first for himself and then for others who admired his exacting craftsmanship. “I worked with Al Nelson and Dave Cheney, building boards for people we knew,” Curren recalled. “This was before stickers. We used a rubber stamp, ‘Nelson Surfboards.’ The guys that put no money down on their boards got theirs first. If they paid in advance they had to wait. That was pretty standard in the industry.”

They were shaping balsa boards in the beginning (before the advent of polyurethane foam blanks were available) in vacant lots, the Windansea parking lot, random garages, and on the beach under the pier. Curren, Nelson, and Cheney tried opening a legit shaping “shop,” but that didn’t last very long.

The lure of The Islands was irresistible once photos of the big surf at Makaha were published in the Mainland press in 1953.

Soon thereafter, the Windansea crew were winging (and sailing) their way to Oahu in search of The Big Blue Wave. The rudimentary, subsistence lifestyle they devised in and around Windansea transposed fluidly to the rural North Shore, which, at the time, was deep Country, composed of a rotting old railroad track that circled the island; some muddy, bumpy dirt roads; a couple overgrown pineapple fields and a cattle ranch at Kaunala (now V-Land); as well as several small subsistence pig and chicken farms run by Chinese and Hawaiian locals in and around Paumalu (Sunset Beach) Northeast of sleepy Haleiwa town.

“Even though occasional surfers had been driving out,” Flippy Hoffman remembers, “no one was actually living (on the North Shore)… There were very few people . . . pig ranchers and shit. Not many Hawaiians either. And they didn’t even look at surfers. It’s like it is today [in] Kahuku — you don’t even know they’re there. And there sure weren’t any haoles. Nothing.”

Humble, hungry, and single-minded, Curren was at the vanguard, living a simple hand-to-mouth lifestyle centered around the ocean.

He first set up a rudimentary camp on a vacant lot next to the beach at Pupukea, near what would be known as the Banzai Pipeline (named by his Windansea comrade Mike Diffenderfer).

Curren was an avid diver and caught most of his food with a spear (Hawaiian sling) or his bare hands (wrestling Honu — sea turtles — to the surface from deep free-dives); otherwise he poached random feral fowl in the bush.

Greg Noll confessed:

“When Pat and I went on patrol, there wasn’t a chicken or a duck that was safe. I can still see us running down the beach at Pupukea with a big fat chicken in each hand, calves burning in the soft sand with a couple of pit bulls on our ass. We’d barbecue ‘em up later and have a hell of a dinner. Pat was also a pretty decent fisherman and a great diver. So between the ocean, the chickens and the ducks, he got along pretty good.”

This set the standard pace for the underground avant-garde North Shore regimen that persisted for decades. Noll declared that Curren “molded it into a state-of-the art lifestyle.”

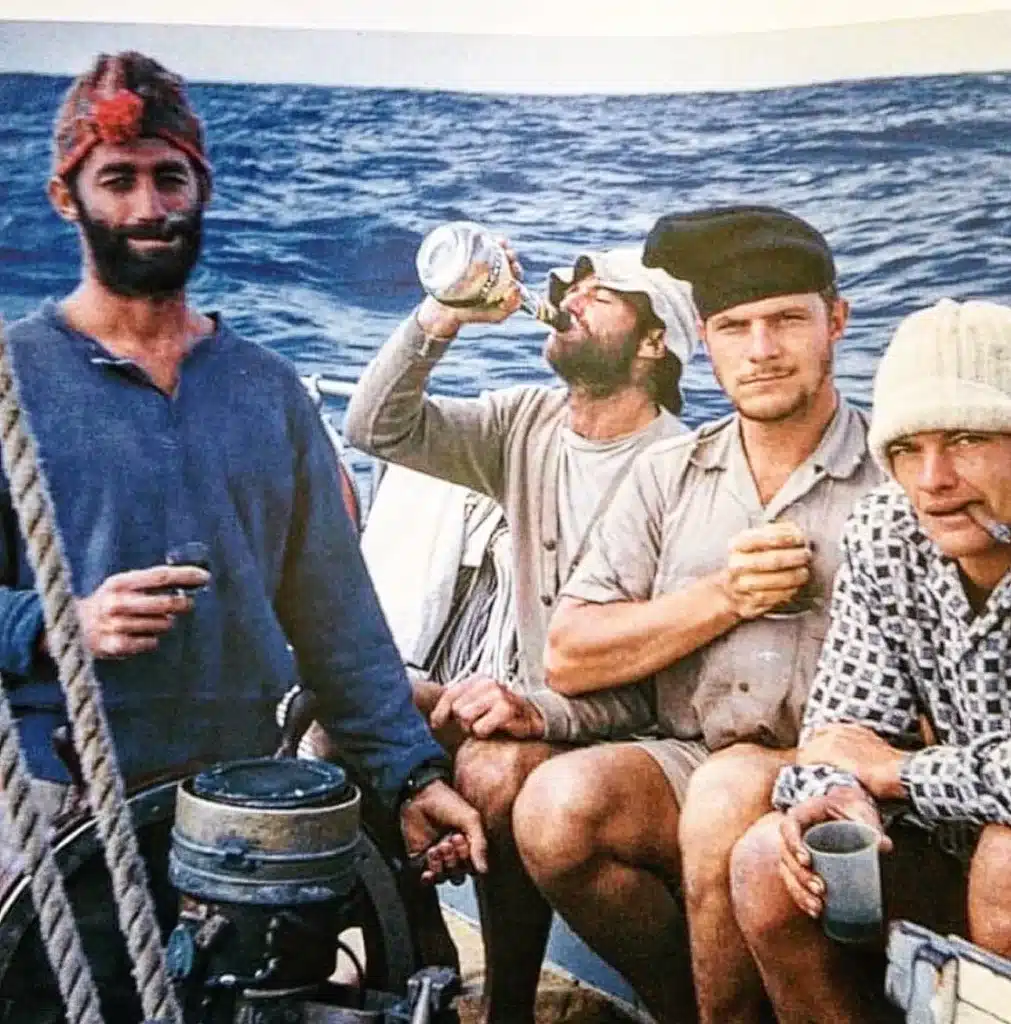

Not long after the improvised beach camp, Pat and some of the Windansea guys rented a dilapidated Quonset Hut on Sunset Point (in what would come to be known as the “Backyards” neighborhood) for $60 a month, living (and arguing) together in a Spartan commune of sorts.

Curren et al. gutted the Quonset hut, knocking out the walls and transforming the structure into an open gallery with surfboard racks floor-to-ceiling on the walls on either side, bunks beneath, and a long slab of a table down the middle. They called it the “Meade Hall” in honor of their (imagined) Viking forbears. Curren proudly presided at the head of the table sporting a Viking helmut with a ryhyton (Scandanavian drinking horn) overflowing with meade (more probably beer) in hand – Skål!

Between 1955 and 1957 the primary focus was on the glorious, challenging, shifting peaks of Paumalu (Sunset Beach) and the elusive Bluebirds at Point Surf Makaha on Oahu’s Westside during the Autumn and Winter months; as well as the smooth, powder blue cloud-breaks off Waikiki in Town (Honolulu) during the summer.

This period was when Pat got serious about building surfboards, taking what he had learned back on the Coast (with Nelson, Cheney, Diff, and a colorful character from Hermosa Beach named Dale Velzy — namesake of Velzyland) to another level of expertise.

Curren’s designs and shaping methods evolved quickly as he adapted to the powerful waves of Oahu. Others soon took notice.

“I really started shaping boards [on my own] in 1956-57,” Pat recalled. “I was walking down the beach at Waikiki and a guy at a rental board place asked me who had made the board I was carrying. I said I did. He asked me to make 20 rental boards. So I rented a shop in Haleiwa and got into it.”

Mike Doyle, a contemporary and champion surfer, recounts:

“What really set Curren apart, and won him the admiration of the others, was that he made the most beautiful, streamlined surfboards any of us had ever seen. Each one of his boards was a cross between a work of art and a weapon, like some beautifully crafted spear. Curren had learned how to attach slabs of wood to the nose and tail of a board to get more rocker, or curve. And his boards went like rockets. In those days, speed was everything. Riding big waves wasn’t about style or looking pretty or making graceful cutbacks or any of that. It was about going for the biggest wave and hoping you didn’t get killed. Curren’s boards were designed to go straight down the line, hard and fast. They gave you a chance at survival.”

Necessity is the mother of invention; and North Shore big-wave riders needed, among other things, more rocker (curve) in their surfboards to accommodate the steep, barreling waves of Sunset Beach, Laniakea, and Haleiwa, as well as the long, precipitous, hollow walls of Makaha — and, soon enough, the beckoning giant combers of Waimea Bay.

Pat was probably the first to put rocker in his boards in the late ‘50s. This innovation was, according to Doyle, “his real genius.”

Additionally, he developed templates out of Masonite so that he could refine and replicate both his outlines and rocker into prototypes of certain gun designs.

Doyle remarked that “Curren developed that template through years of big-wave riding, countless wipeouts, who knows how many scars and bruises, endless hours at a drafting table, plus an enormous amount of natural talent.”

These developments, tweaks, and improvements in shapes and designs instigated a paradigm shift in the evolution of modern big-wave-riding equipment.

Nineteen fifty-seven marks yet another huge leap forward into the relatively unknown — and unridden — realm.

Up until that point, Waimea Bay remained strictly Kapu: sacred, forbidden, and foreboding. The conventional wisdom, even among these pioneer Devil-may-care iconoclasts, was that the Leviathans of Waimea couldn’t be surfed or survived: at once unridden and unrideable.

An ominous mystique surrounded the Bay as a place that was not only haunted by ancient Uhane (ghosts) and swarming with ravenous sharks, but also the spot where Dickie Cross drowned (lost at sea: no body was found) back in 1943.

Cross and his comrade Woody Brown had to paddle three miles down the coast from massive, closed-out Sunset Beach only to find, as the sun set, that the Bay itself was also shutting down.

Giant 60’-plus faced waves detonated a half-mile outside the beach, the Bay itself a roiling cauldron of deadly rips. Brown chanced paddling in between the gigantic sets and somehow got washed in (naked) sans board in the misty twilight; whereas Cross was never seen again. The prevailing wisdom thereafter was that Waimea was off-limits, not worth the risk.

That all changed one halcyon afternoon on November 5, 1957. Some of the boys, including Greg Noll, Mike Stang, Micky Munoz, Diffenderfer, and Curren, among others, were sitting in their jalopies looking at relatively smooth, clean inviting peaks outside the point of Waimea Bay and decided to give it a shot.

It was by no means giant or death-defying, but it was a major step forward in the progression of big-wave riding. After they paddled out and caught (although didn’t really make) a few waves, the spell had been broken.

Despite their best efforts, however, most everyone either got pitched over the falls, pearled, or, if they made the drop, their crude, straight (rockerless) longboards popped out of the water.

No one actually made a wave. Curren realized immediately that he (and the rest) needed something even more refined and specialized in order to successfully surf these big waves. The “ultimate gun” was required; and Pat was the man to make it.

Echoing Brewer’s testimony, Peter Cole affirmed that “Pat was the first guy to produce the ultimate gun [before Brewer and Diffenderfer]. Joe Quigg and Bob Sheppard were making nice boards for all-around surfing, but Pat made the stiletto, specifically for Waimea, where you go from Point A to Point B on the biggest wave that comes through.”

If one was serious about catching and successfully riding the biggest waves, one required a Curren gun. It was as simple as that. Pat forged the path that all the rest would follow in the years to come.

“No question about it,” certified Ricky Grigg: “He was the best shaper. Number one. He had a real concept of the elephant gun. First guy to shape it, first guy to ride it. He was so respected, he had a cult following. He was a guru.”

Top Gun. Non Plus Ultra.

A reluctant, recalcitrant guru at that. Never one to seek the limelight or court photographers and attention, Curren nevertheless was thrust into the role of a leader, as Homer’s Peleus – valorous father of Achilles – said of his outstanding son: “always out front, the best, outstripping others. Leader of the pack.

“He didn’t want to be, though,” Peter Cole noted. “That was the amazing thing. He did not want to be a leader. I think guys just gravitated to him.”

Not only quiet, he was often silent. The enigmatic Curren would go for an entire day without saying a word. Nor was he the robust physical specimen that, for example, Buzzy Trent exemplified with his chiseled physique and ripped muscles. Doyle (a self-styled golden-boy) brazenly described Curren as “gaunt and pale, with a pointed chin, sunken cheeks, and worried eyes . . . real quiet and moody.”

Perhaps it was an off day, hungover; in the photos I’ve seen of the young Pat, he looks ripped, vigorous, and strong. He was also one with the ladies, according to Fred Van Dyke, who reported that “he had an incredible effect on women . . . they’d just fall apart” in his presence. Notwithstanding his modesty, reticence, and reserve, Curren was also renowned as sly, playful, and funny, sharply witted, always up for a prank.

Many of the North Shore pioneers trained regularly, obsessively one might say, and worked hard to stay in top shape. The Adonis Buzzy Trent was perhaps the best exemplar of such rigorous practice — one of the original “Surf Muscles” (cf. ironmen past & present such as “Tarzan” Smith, Jeff Hakman, Sam Hawk, Laird Hamilton) – but there were others, including paddle-board champions Tom Zahn and Doyle, as well as the burly Van Dyke, who would train together during the Summer at Ala Moana in Town when the surf was flat, racing each other on paddle-boards, swimming laps, and sprinting the beach.

True to form, the nonconformist Curren wasn’t a fitness freak, regardless of the fact that he could free-dive to depths of 60’ or more and handle himself confidently in heavy water situations. He preferred cigarettes, cold beer, and a barbecue on the beach of fish or fowl he freshly caught to harried calisthenics, tedious beach runs, and running out of breath. Altogether disinterested, the self-deprecating Curren described himself as a “shitty athlete.”

One afternoon, however, enjoying a cool two-beer afternoon buzz, Curren took a long draw on his cigarette, stubbed the butt into the sand and challenged the plucky teetotaler Tommy Zahn to a paddle competition.

The vivacious Zahn laughed in his face and accepted the dare with a dismissive snark. Curren proceeded to smoke the vainglorious jock, leaving Zahn sucking wind in his wake as Pat pulled hard across the Ala Wai. Chastened and defeated, Zahn was mortified, on the verge of tears. When Pat got back to shore, he kicked back, cracked another brew, and sparked a Lucky Strike.

So it went for the next several years, during which time the quietly reserved Curren ascended and was recognized by all as the undisputed “King of the Bay.”

Waimea Bay. Top Gun. Non Plus Ultra.

There were standout days, such as January 10, 1958, when the Bay reached epic closeout conditions (30’ plus = 60’ plus faces) as big and rideable as it gets. A few days later (Jan. 13-14), the entire North Shore washed out (40’ or more) and Point Surf Makaha came alive for the intrepid few.

Curren was the standout surfer on the Bay day; John Severson at Makaha. Not surprisingly, Curren considered those years in the late ‘50s – pristine empty lineups with no crowds, cheap rent, an ocean teeming with an abundance of free food, and an endless supply of powerful, perfect waves — as being the “best time of my life.”

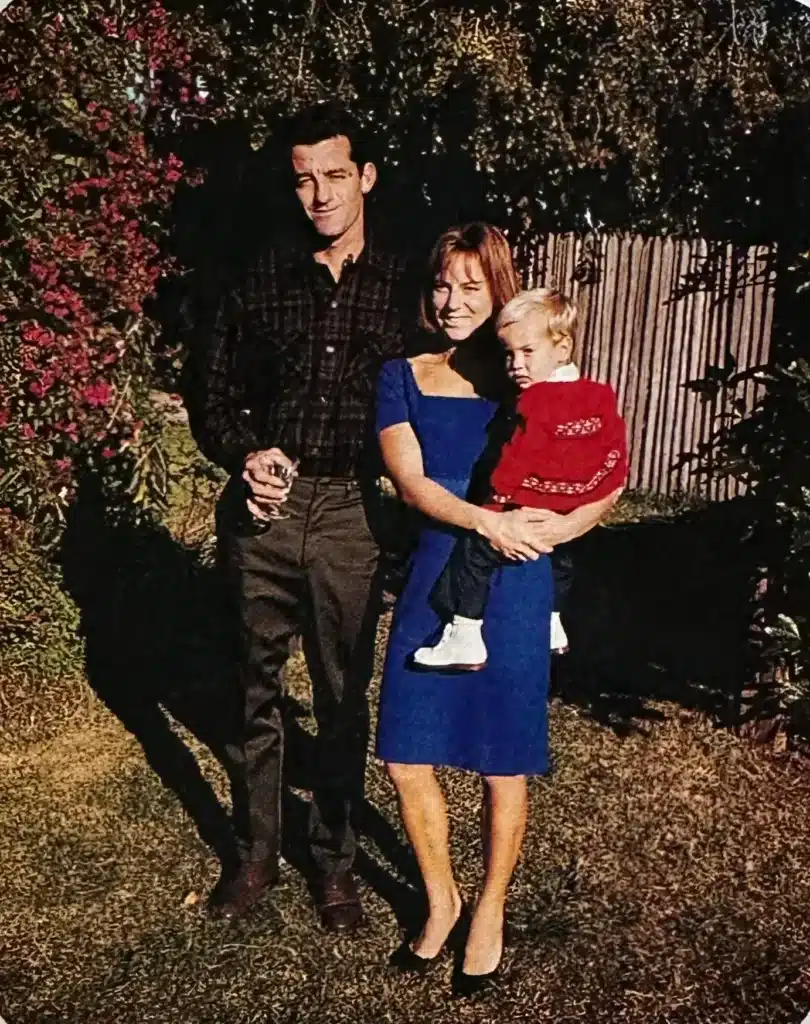

Curren met a gal named Jeanine in 1960 and they married the next year. She would, in her words, inevitably “steer his energy away from the North Shore.” They were married in a small, private ceremony at Maile Point on the Westside with a few local Hawaiians, including Sammy Lee (who loaned Pat his tuxedo jacket, which was a little too big for the groom), his best man Jose Angel, and Buzzy Trent in attendance.

The surf was pumping that day, so after the ceremony, guns stuffed in the back of his woody, Pat along with his newlywed, Sammy, the Angel and Trent families headed back to the North Shore to surf Waimea Bay.

Jeannie remembers that she “spent my wedding day wondering if my husband was going to come back alive.”

A year or so later, as the North Shore became increasingly popular, busier with crowds of surfers, more and more people settling, putting down roots, and building homes, Pat (now 30 years old) was over the hype and ready for a change. He felt like he had achieved what he needed in terms of both his surfing and shaping aspirations; there was nothing else to prove.

He determined that: “The Islands were too crowded . . . and I was getting ready to do something else. I’d done everything I wanted to do there. I pretty much gave up surfing in 1962.”

The Currens moved back to the mainland.

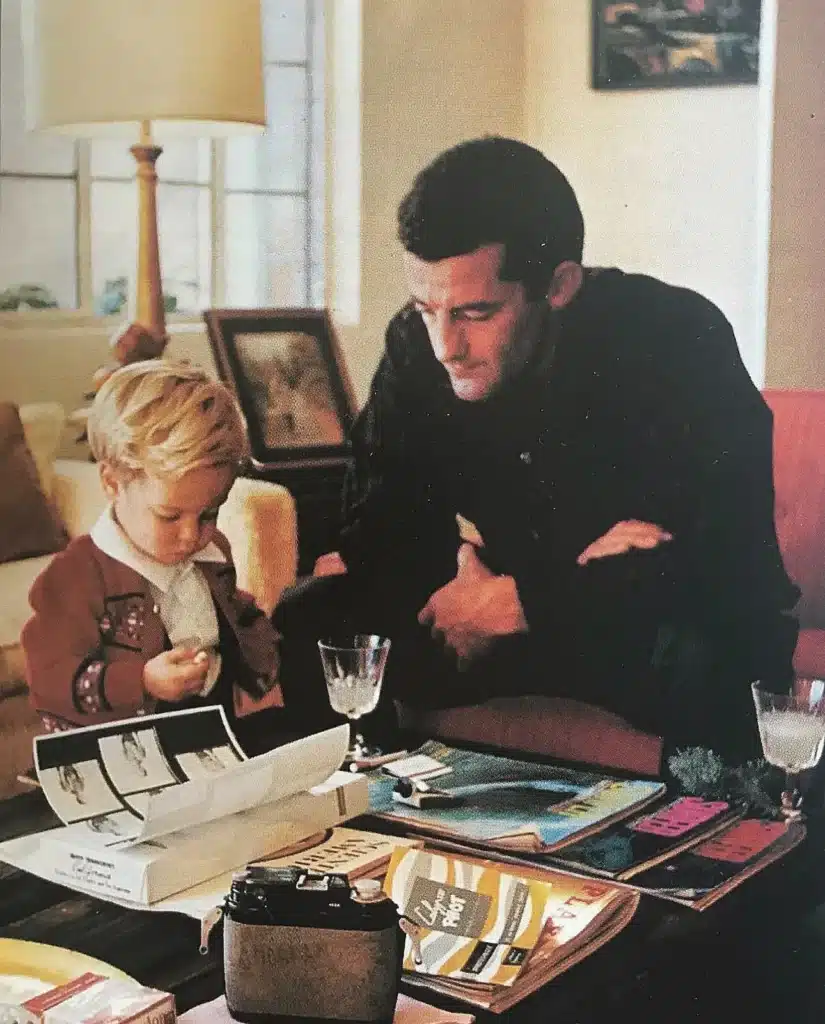

They settled in Newport, where they had their first son. His name was Tom and he would go on to become one of the greatest surfers of all time, a three-time world champion, as well as an accomplished musician; one of the most revered figures in surfing history.

Owl told me a funny story about the day Tom was born. In July of 1964, the not quite 14-year old Craig (a.k.a. Owl) was a full-on surf-stoked gremmie, living in Costa Mesa, across the Coast Highway from the beach. He, his older brother Gary (a.k.a. Chappy) along with some friends (including Dave Abbott, Walter Visolay, and Mike Taylor), had a little club-house, called “The Shack,” near the beach in Newport (30th / 40th Street?) which they built together, where they’d hang out, smoke cigarettes and the occasional “reefer” between surf sessions.

Pat had a shaping room and surf-shop next door to the groms’ “Shack.” One afternoon that summer, the day before the Fourth of July, Curren ambled in, covered in foam and sawdust, bummed a cigarette from one of the kids, sparked up and sat there a while silently, then stated brusquely: “My wife just had a kid.”

The way Owl tells the story, Pat didn’t seem all that thrilled about the event. Truth is often stranger than fiction.

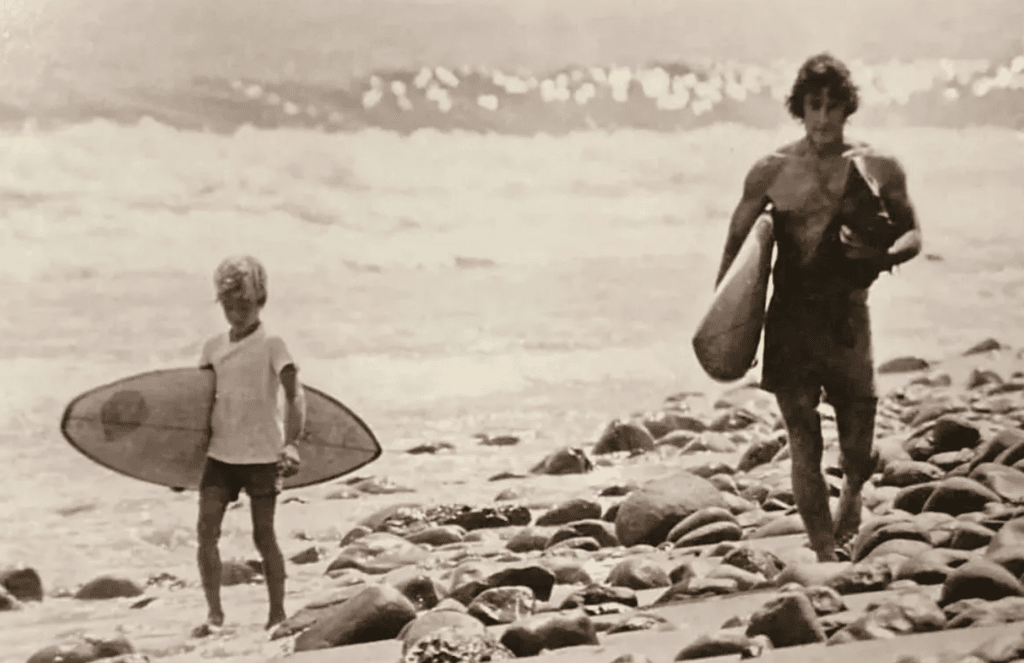

Not long afterwards, the Currens relocated up the Coast to Santa Barbara, in Carpenteria. They had another boy named Joe in 1974; a sister Anna was born some years after that. Pat gradually found his way back to the ocean and surfing in the ‘70s, enjoying the waves with his son Tom (for whom he built custom surfboards) at the fabled points of the region: Hammonds, Rincon, El Capitan, the Ranch.

Tom remembers:

“My dad really went out of his way for us to see different parts of the world. Hiking, horseback-riding, we did all this stuff. He definitely enriched our lives . . . and especially me because I was the oldest. That influenced me, at least with my own kids to show them things that might jar them in a pleasant way . . . He got me surfing…”

Meanwhile, Jeannie found Jesus and religion; while the burgeoning adolescent Tom discovered, among other things, marijuana, as well as his independence.

Frustrated and feeling penned in by various pressures of society and the challenges of family life, Pat withdrew.

Jeannie lamented that “he saw our life as an impossible situation. I could sense the sadness come over him.”

“He made a toolbox, put his tools in it and said ‘goodbye’. . . He was discouraged; and he didn’t know what else to do, so he went out into the wilderness . . . his pride — that’s what keeps him there.”

The marriage fell apart in 1981.

“We could see it coming,” said Tom. “I was surfing all over California at the time and didn’t see him that much, and I handled it fine. When you’re seventeen years old, it isn’t a major trauma. It was hard on him though. Hardest thing he’d ever been through.”

Pat split South to Costa Rica, where he enjoyed a surfing renaissance in Central America long before the invasion of hordes of ex-pats and tourists.

In the late ‘80s, he migrated back up to the Southern tip of Baja, on the East Cape. I remember hearing hushed, word-of-mouth stories trickling in through the coconut wireless during the early ‘90s (around the time I first beheld that beautiful gun in JR’s shop) of Curren living solo out of his camper-truck, surfing perfect, hollow rights at a fabled secret spot called Boca de Tule. He lived the life of loner exile for years, surfing the early morning glass until it blew out. A legend.

He would have a fourth child, a daughter named Maile, some years later. Pat found his way back stateside and began shaping custom surfboards for those who could find him and afford his rarefied, multi-stringered balsa guns, in addition to scaled-down miniature replicas of the real thing.

Although the surfboards sold for as much as $25K each (a few hundred a pop for the little guys), Pat never seemed to have much money and remained in a perpetual state of pecuniary need. A few years ago (2020), his son Joe lamented:

“Yes, it’s true, he struggle[ed] financially. The truth is, this ha[d] been going on for a long time. . . We love and care about my dad very much . . . [and] we’ve always respected my dad’s wish to keep this kind of stuff private . . . My brother Tom and I, my sisters Anna and Maile, my dad’s brothers Mike and Terry and the entire family have all been trying to help him, doing the best we can, for years and years. It has been challenging and complicated; and we always run into a major road block.”

The last couple of decades saw Curren traversing back and forth across the border, always close to the ocean, struggling perennially to elude the crowd and live life on his own terms.

Pat himself put it like this: “We keep gettin’ pushed into these little corners. The last time I surfed Malibu had to be 1952. Couldn’t believe how crowded it was. Never went back. La Jolla got all fucked up, then Hawaii, then Costa Rica. I’m runnin’ out of places. Then again, I’m runnin’ out of time.”

Epilogue:

In my surfing life I’ve had the profound privilege and pleasure of meeting and surfing with many icons of surfing. Some of them, such as Peter Cole and Ricky Grigg, I even got to know and called friends. I’ve learned valuable lessons from each in various ways, more than grateful to share the lineup and some insights.

Yet, there are two guys that stand head and shoulders above the rest, in terms of the awe and gratitude inspired in me: Dick Brewer and Pat Curren.

These two surfer-shapers achieved and contributed more to the legacy of what’s been made possible in giant waves of consequence than anyone else I can think of — Pat lit the proverbial torch (in terms of pushing the envelope of big-wave-riding shaping and surfing potential) and passed the torch to RB, who grabbed it and took off running . . . The rest is history.

We lost them both in the past year, along with many others, notably including Paul Gebauer, Joe Quigg, and Greg Noll, each and all of whom were both friends and admirers of Pat. Seasons change. The Moon wanes. Tides ebb. The Sun sets . . . Eternal recurrence of the same.

Patrick King Currren died on Sunday, January 22, 2023.

It was an exceptional day. Powerful, glorious, and ferocious. The surf on Oahu was giant and Waimea came alive, really showed its teeth. It was absolutely pumping 20’-25’ (occasionally bigger) from dawn until dusk. Biggest, cleanest, meanest Waimea in decades, almost, truth be told, too big.

The Pat Curren Swell? Why not. Sounds about right.

It was an Epic Day of surf. Perfect offshore conditions Island Wide all day long. While I attempted to ride gaping 15’-20’ Point Surf Makaha, they held the Eddie Aikau Invitational and local-boy lifeguard, underground charger Luke Shepardson won the event in classic, Pat Curren form — a quiet, deserving, homegrown underdog defeated or overcame the best of the best: John Florence, Mark Healey, Billy Kemper, et al.

All of them links in a chain that extend back directly to Pat Curren, the original King of the Bay. The First Top Gun.

He was 90 years old.

We are all born to die. Perhaps the only certainty there is in this existential Odyssey we call life. It’s what one does between birth and death that marks the significance and quality of existence.

In the case of Pat Curren, he accomplished some things rather extraordinary, singular, truly heroic, and simply beautiful on his own terms in his own time, just like those big, beautiful, blue waves he courageously charged and that exquisite balsa gun I saw in Jack’s shop over 30 years ago.

Editor’s note: Subscribe to Andy St Onge’s Substack here. It’s wrapped in wild North Shore stories.